Motivational Interviewing Skills & Client Responses Analysis

Anuncio

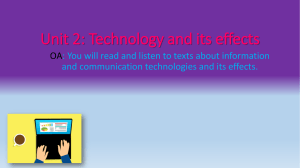

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author Manuscript J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Published in final edited form as: J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018 September ; 92: 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.006. A sequential analysis of motivational interviewing technical skills and client responses M. Barton Lawsa,*, Molly Magillb, Nadine R. Mastroleoc, Kristi E. Gamareld, Chanelle J. Howee, Justin Walthersb, Peter M. Montib, Timothy Souzab, Ira B. Wilsona, Gary S. Rosef, and Christopher W. Kahlerb aDepartment of Health Services, Policy and Practice, Brown University School of Public Health, Author Manuscript Providence, RI, United States bDepartment of Behavioral and Social Sciences and the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, RI, United States cCollege of Community and Public Affairs, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY, United States dDepartment of Health Behavior and Health Education, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, United States eDepartment of Epidemiology, Centers for Epidemiology and Environmental Health, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, RI, United States fWilliam James College, Newton, MA, United States Author Manuscript Abstract Author Manuscript Background: The technical hypothesis of Motivational Interviewing (MI) proposes that: (a) client talk favoring behavior change, or Change Talk (CT) is associated with better behavior change outcomes, whereas client talk against change, or Sustain Talk (ST) is associated with less favorable outcomes, and (b) specific therapist verbal behaviors influence whether client CT or ST occurs. MI consistent (MICO) therapist behaviors are hypothesized to be positively associated with more client CT and MI inconsistent (MIIN) behaviors with more ST. Previous studies typically examine session-level frequency counts or immediate lag sequential associations between these variables. However, research has found that the strongest determinant of CT or ST is the client's previous CT or ST statement. Therefore, the objective of this paper was to examine the association between therapist MI skills and subsequent client talk, while accounting for prior client talk. Methods: We analyzed data from a manualized MI intervention targeting both alcohol misuse and sexual risk behavior in 132 adults seen in two hospital emergency departments. Transcripts of encounters were coded using the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC 2.5) and an additional measure, the Generalized Behavioral Intervention Analysis System (GBIAS). Using * Corresponding author at: Department of Health Services, Policy and Practice, Brown University School of Public Health, G-S121-7, Providence RI 02912, United States. [email protected] (M.B. Laws). Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.006. Laws et al. Page 2 Author Manuscript these measures, we analyzed the association between client talk following specific classifications of MICO skills, with the client's prior statement as a potential confounder or effect modifier. Results: With closed questions as the reference category, therapist simple reflections and paraphrasing reflections were associated with significantly greater odds of maintaining client talk as CT or ST. Open questions and complex reflections were associated with significantly greater odds of CT following ST, were not associated significantly with more ST following ST, and were associated with more ST following CT (i.e., through an association with less Follow Neutral). Conclusions: Simple and paraphrasing reflections appear to maintain client CT but are not associated with transitioning client ST to CT. By contrast, complex reflections and open questions appeared to be more strongly associated with clients moving from ST to CT than other techniques. These results suggest that counselors may differentially employ certain MICO technical skills to elicit continued CT and move participants toward ST within the MI dialogue. Author Manuscript Keywords Change talk; Motivational interviewing; Sequential analysis; MI technical skills; Sustain talk 1. Introduction Author Manuscript Motivational Interviewing (MI) is among the most widely-used approaches to effect behavior change. It was originally developed in the 1980s to address alcohol misuse (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). It has since been extended to other behavioral domains, and metaanalyses have found it to be effective for many targeted behavioral changes such as physical activity and medication taking (Lundahl & Burke, 2009). However, effect sizes are highly variable, and not all trials show effectiveness (Ball et al., 2007; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Miller, Yahne, & Tonigan, 2003; Winhusen et al., 2008). This has spurred interest in gaining a better understanding of the mechanisms of behavior change in MI to optimize its effectiveness. Author Manuscript A central hypothesized mechanism in MI is client motivational language. Specifically, the technical hypothesis proposes that “change talk” (CT) — client speech during the session that indicates motivation, preparation, and commitment to behavior change — is associated with better behavioral outcomes, whereas talk against change —counterchange, resistance, or “sustain talk” (ST) — is associated with less behavior change. There is growing evidence supporting the relationship between client CT and behavioral outcomes (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009; Miller & Rose, 2009; Moyers et al., 2007). Yet, some studies find more specific or limited relationships, suggesting these may be complex associations requiring increasingly nuanced methodologies. At an aggregate level, meta-analyses show more ST is associated with less behavior change, a combined measure of CT and ST is associated with more behavior change, and CT alone does not have a predictive effect (Magill et al., 2014). Another recent meta-analysis similarly found that ST was associated with worse MI outcomes, and the effect for CT was non-significant (Pace et al., 2017). Perhaps the most distinctive contribution of the MI theoretical literature is the technical component, which underscores the importance of identifying, eliciting, and reinforcing J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 3 Author Manuscript client CT. An early principle in the development of MI was that arguing against resistance, or confrontation, is counterproductive as it tends to elicit more resistance, in part because it limits patients' perceived autonomy (Moyers, Miller, & Hendrickson, 2005). Practitioners highly skilled in delivering MI successfully elicit CT, identify various types of CT, and reinforce CT through the use of skillful reflective listening, while also “rolling” with client resistance.(Miller & Rollnick, 1991). Author Manuscript Several studies have evaluated processes occurring in MI sessions to determine whether the technical component of MI operates as hypothesized. Evaluations of MI processes typically utilize the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) (Miller, Moyers, Ernst, & Amrhein, 2003), and subsequent versions and extensions of the system. In the MISC, specific counselor verbal behaviors are encoded and can be classified as MI consistent (MICO) and MI Inconsistent (MIIN). Subsequently, the relationship between MICO and MIIN categories and client CT and ST can be examined, typically in correlations of session-level frequency measures or in sequential analyses. Sequential models, which preserve the temporal sequence between counselor behaviors and client responses, may provide a more specific estimate of how therapists elicit motivational statements within clients. In fact, although effect sizes for the correlation between MI skills and client change statements are “moderate”, they are “small” when temporal precedence is taken into account (Magill et al., 2014). Author Manuscript Sequential analyses of how MI skills are associated with subsequent client language have numerous conceptual and methodological strengths allowing for a more direct examination of the technical hypothesis than cross-sectional analyses. However, there are also some limitations and challenges with such investigations. Conceptually, a sequential model derives probabilities that certain types of statements will follow certain types of statements from the other speaker in a predictable manner. The method was popularized in the marital therapy literature by John Gottman and colleagues in the 1980s. In the MI literature, a body of sequential research emerged via the development of the Sequential Code for Observational Process Exchanges (MI-SCOPE) (Martin, Moyers, Houck, Paulette, & Miller, 2005). In these studies, the types of client statements of interest are typically summary measures such as CT, ST, and utterances which are neither (i.e., Follow Neutral [FN]). Therapist utterances could be classified as MICO or MIIN, or more specifically, if frequency of occurrence allows. In sequential analysis, these labels can be called “states” and the relationship between an utterance and the following utterance is termed a “transition.” These therapist behaviors can be called “elicitations.” Author Manuscript Sequential analyses have the capacity to extend our understanding of the association between counselor technique and client response. For example, an analysis of data from a smoking cessation intervention in Sweden (Lindqvist, Forsberg, Enebrink, Andersson, & Rosendahl, 2017) found that clients were more likely to produce CT following MICO behaviors and questions and reflections favoring change, and were more likely to produce ST following reflections of ST. This study also found that MIIN utterances were not more likely than chance to be followed by ST, but rather by FN. They speculate that this may be because ST did not occur at lag one, but did occur later. J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 4 Author Manuscript Another study that computed all transition probabilities using categories from the MISCOPE found that reflections of change talk were more likely to be followed by change talk than by chance, and that reflections of counterchange talk were also more likely to be followed by counterchange talk (Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009). These authors conclude that “To obtain better outcomes using MI, clinicians should attend carefully to client language about change and use strategies recommended in the practice of MI (asking questions likely to result in change talk, reflecting change talk when it occurs, and emphasizing client choice) to gain more of it. (p. 1121). Author Manuscript A study of MI for alcohol treatment found that reflections of CT were likely to be followed by CT, and that the probability of CT followed by CT in the next client utterance was associated with reduced drinking (Houck & Moyers, 2015). Two studies that examined all transition types (e.g., therapist to client, client to client, client to therapist), found that in client-to-client transitions the previous client state was more strongly associated with the subsequent client state than was any intervening therapist elicitation (Gaume, Bertholet, Faouzi, Gmel, & Daeppen, 2010; Romano, Arambasic, & Peters, 2017). A study of a group MI intervention for adolescents found that open questions and reflections of change talk were more likely than change to be followed by change talk, that reflections of sustain talk tended to suppress subsequent change talk, and that change talk by group members was more likely than chance to be followed by more change talk. This situation is not directly comparable to individual counseling since the previous “client state” may not have been produced by the same person who makes the next client utterance, but does reinforce that it may be important to distinguish among MI consistent therapist behaviors and to account for the context in which they appear (D'Amico et al., 2015). Author Manuscript This work suggests we are making progress in understanding the MI technical component via sequential modeling and when the odds of specific client responses are of interest, it is important to take into account the prior client state. Author Manuscript Sequential analyses at more than one lag can be computationally intractable because the number of transitions increases exponentially with additional lags. For this reason, sequential analyses typically examine only the transition between one utterance and the one immediately following. However, the first MISC-coded statement within a longer series of utterances will not necessarily capture the crux of the client's verbal intent. We argue the sequential model should account for all client statements between a given therapist elicitation (i.e., question or reflection) and the next. Moreover, the last client CT or ST utterance in the sequence may best represent the overall direction of the response toward or away from behavior change. Consider the following example from the data used in the present study. (I = Interventionist, P = Participant): I: So tell me about that experience, what it's like the next day. P: You don't wanna be like that. But, I mean, that's when I start regretting it and then, uh, you know, we [referring to her friends] talk about it and I say, you know, I probably wouldn't have done that if we not were drinkin', but doesn't bother us enough to stop (laughter). J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 5 Author Manuscript The initial utterance following the counselor's elicitation (in this case an open question) would be coded as CT. However, the participant's final utterance is ST indicating that she is not ready to change in spite of negative consequences. Author Manuscript The purpose of the present study is to build upon the prior sequential model literature by examining the relationship between therapist elicitation interventions and subsequent client motivational statements – CT, ST, or FN while taking into account clients' prior state. We use an expanded model that incorporates all client utterances following an elicitation “episode” up to a defined therapist behavior that terminates that episode (please see Methods for further description). We incorporate the client's previous state (i.e., whether the prior episode is labeled as ST, CT, or FN) as an effect modifier, with the hypothesis that the odds of elicitations resulting in subsequent client language will depend upon the client's prior state. Finally, because MI therapist elicitation interventions are of primary interest, we extend the commonly used classification grouping for therapist skills to include a more comprehensive typology identified within the MI-SCOPE (Martin et al., 2005). We expected that some techniques would be more likely than others to be associated with transitions from ST to CT, while others might be associated with maintaining the prior state. The goal of this work is to provide MI therapists with specific guidance on how MI techniques can function in eliciting a range of client motivational responses. 2. Material and methods 2.1. Parent trial description Author Manuscript This study is based on analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial of a brief (one session) MI intervention, compared to a brief advice control (Monti et al., 2016). Patients were not treatment seeking, but were recruited during visits to two Emergency Departments (EDs). The intervention targeted both risky alcohol use and sexual behavior. Patients age 18–65 were screened using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De la Fuente, & Grant, 1993), and completed a questionnaire on drinking and sexual risk behavior. Eligible subjects scored ≥8 on the AUDIT (males) or ≥6 (females), or endorsed at least one episode of binge drinking in the past 30 days (≥ 5 drinks for males, ≥ 4 drinks for females); and reported engaging in at least one sex risk behavior in the past 3 months. Behaviors included having condomless sex with a non-steady partner, condomless sex with a steady partner where infidelity was suspected, and having sex under the influence of alcohol or other drugs. Author Manuscript Patients completed the screening, enrollment, and baseline assessment while at the ED, and were then randomized. They completed the MI session in the ED within 2 weeks of the baseline assessment. One hundred eighty four study participants were randomized to the MI condition, of whom 169 completed the session. The sessions were audio-recorded and later transcribed for coding and analysis. Of the 169 transcripts, 132 were randomly selected to be coded for this study due to resource limitations. The manualized MI session consisted of components including open-ended exploration of the pros and cons of drinking and risky sexual behavior, feedback and normative comparisons drawn from responses to baseline assessments, and change planning for clients J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 6 Author Manuscript who were interested. The structure of the intervention was such that the therapists were instructed to intentionally elicit both CT and ST in the early part of the session (i.e., ambivalence exploration), before transitioning to a focus on solidifying motivation in the direction of change (i.e., reduced alcohol use and sex risk behaviors). The change plan, when it occurred, also typically required that therapists engage in some intentional elicitation of ST in order to identify possible barriers to change and develop solutions. Sessions were typically 60 min in length, and participants were compensated with $50. Therapists received 20 h of training, including didactic presentations and simulated roleplays, and received ongoing group supervision with review of audio recordings of sessions. Author Manuscript The intervention, compared with brief advice and controlling for baseline covariates, was associated with fewer heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per week, and overall reduced likelihood to engage in excessive drinking over 6 and 9 month follow-ups. It was also associated with lower odds of reporting condomless sex with a casual partner, and fewer days of sex under the influence of alcohol and/or other drugs (Monti et al., 2016). 2.2. Process measurement, procedure, and process variables of interest As detailed in the MISC, therapist behaviors can be classified as MI-consistent (MICO) or Mi-inconsistent (MIIN). MICO behaviors include Affirm, Advise with Permission, Emphasize Control, Raise Concern with Permission, Support, Open Questions, and Reflections (simple or complex). MIIN Behaviors are Advise without Permission, Confront, Direct, Raise Concern without Permission, and Warn. Additional, or “Other” practitioner behaviors include Closed Questions, Giving Information, Structure, and Facilitate. Author Manuscript For the present study, we developed additional therapist skill codes to extend and enhance the information provided by the MISC 2.5 (Houck, Moyers, Miller, Glynn, & Hallgren, 2010), some of which is analyzed and described elsewhere within the Generalized Behavioral Intervention Analysis System (GBIAS) (Kahler et al., 2016). Coding manuals are available at https://doi.org/10.7301/Z0Z60MKW. The speech act component of the GBIAS is based on the Generalized Medical Interaction Analysis System, which is described in detail elsewhere (Laws et al., 2013; Laws et al., 2014). The GBIAS assigns specific codes to what would otherwise be undifferentiated therapist and client utterances within the MISC, and includes categories for speech acts such as representations of facts, deductions or conclusions, self-reports of behavior, or expressions of affect. The additional content of relevance to this report includes an expanded typology of therapist elicitation behaviors, which are described in detail in Table 1. Author Manuscript In the GBIAS, simple reflections, as in MI systems, are defined as restatements of client speech with no change in meaning – often literal echoing. By contrast, paraphrasing reflections repeat content of client speech with some small extension of meaning. Examples of these are given in the MISC manual but they are not given an explicit label, but rather conflated with complex reflections generally. An example would be: Client (C): Like, I just, I'm such a paranoid person, it's [drinking] helpful. Therapist (T): So for you, you know, you have that little bit of anxiety around people, and alcohol is a way to kind of help lessen that anxiety for you. J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 7 Or: Author Manuscript C: Drinking makes it so much easier for me to talk to new people. T: You're more social and less nervous around new people when you drink. (These are the role designations given in the MISC manual, not the ones we use here.) The theoretical intent is to test the therapist's interpretation of the client's statement without the directiveness of a closed or leading question. However, if these therapist utterances are said with a rising (questioning) inflection, they are not coded as reflections but as leading questions, which are treated as closed questions in this analysis. Author Manuscript More elaborate forms of complex reflection are classified in the GBIAS similarly to the MISC manual. As these forms of complex reflection were individually fairly uncommon, we combined them for analysis. (See Table 1.) In the MISC, however, they are conflated with what we call paraphrasing reflections, and with summarizing reflections. In a summarizing reflection, the therapist pulls together highlights of a complex story told by the client, perhaps over several preceding turns, in a succinct restatement. This usually brings a topic to a close and signals a new direction for the dialogue, rather than necessarily being intended as an elicitation. Since it typically includes reflections of both CT and ST, client agreement cannot necessarily be given a valence as either CT or ST. Author Manuscript Consistent with the MISC, we consider a facilitative utterance as a brief, often non-lexical utterance such as “uh-huh,” which merely signals that the speaker is listening and continues to cede the floor to the speaker. Words such as “yeah” and “okay” often have this function and do not necessarily signal agreement. Simple reflections have essentially the same function but are encouraged as they are assumed to provide a stronger signal of active listening. Finally, the GBIAS labels the therapist speech act “ask for permission,” and various forms of advice or instruction (e.g. directing, suggesting, disapproval of a behavior), allowing the MICO behavior “advise with permission” to be constructed from a sequence of speech acts. For purposes of this study, we used the MISC coding of participant utterances as CT, ST, or FN, and did not distinguish further. Only 1.6% of MISC-coded therapist behaviors were MIIN (range 0–7.3 per session). The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between various therapist elicitations – the MI consistent behaviors – and transitioning between previous participant CT, ST, and FN, and subsequent client talk. Author Manuscript 2.3. Coder training A total of 7 coders participated over the course of the study. They held master's degrees in psychology, linguistics, or relevant fields. Coders received about 60 h of training on both the GBIAS and MISC systems. Training involved an initial didactic session, individual and group practice with corrective feedback, and coding of the same material by multiple coders followed by discussion and resolution of discrepancies. This process also served to refine the J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 8 Author Manuscript coding manuals. Some coders exclusively did MISC coding, and some did both GBIAS and MISC. Coders listened to the audio of the encounters while coding transcripts. 2.4. Coding reliability Author Manuscript Inter-rater reliability was assessed continuously throughout data collection. After coding every fifth session, a segment of at least 300 utterances was randomly chosen from completed interviews and assigned to a randomly selected second coder. Reliability and agreement statistics were computed and disagreements discussed in bi-weekly meetings. Nineteen encounters were randomly selected for doublecoding. For the MISC double coding of utterance-level data, the mean kappa statistic was 0.79, which indicates substantial agreement (Cohen, 1960). Additionally, the majority (79.6%) of item-level Intraclass Class Correlation values for the codes used in this study were in the “good” to “excellent” range (Chicchetti, 1994). Results for GBIAS speech acts were similarly good, with reliability at the integer level k = 0.82, and k = 0.70 for the second digit, the lowest level used in this analysis. 2.5. Definition and classification of “episodes” Author Manuscript We defined an “episode” as all client statements beginning after a therapist elicitation and ending with the client utterance immediately preceding either the next therapist elicitation, or other therapist behaviors that terminate the client's train of association, including factual representations, therapist expression of his or her own opinions, and overt topic closures or changes; or client topic changes or questions. We classified elicitations as closed questions (the reference category in analyses), open questions, paraphrasing reflections, other complex reflections listed in Table 1, and summarizing reflections, along with advice with permission. We ignored facilitative utterances and simple reflections on the assumption that these do not function as elicitations per se but merely encourage the client to continue on his or her own course. (We tested this assumption in the analysis as described below.) We called client episodes consisting of more than one MISC-coded utterance “multiple episodes.” When these utterances consisted entirely of CT, ST, or FN, they were labeled accordingly. Episodes including both CT and ST were classified according to the last CT or ST statement in the episode, based on the presumption that the episode's terminal utterance is the best indicator of its overall thrust of meaning, and also provides the baseline state for the subsequent episode. To make this determination we examined a randomly chosen sample of 20 mixed episodes and found this presumption to be most consistent with the observed data. Author Manuscript Simple reflections are often included with other MICO behaviors in a summary measure, and their association with CT and ST is tested. However, we believed that simple reflections function similarly to facilitative utterances and simply tend to maintain a given line of participant speech. As shown in Table 2, analysis of episodes in which facilitative utterance and simple reflections were considered as therapist elicitations were consistent with this supposition. Following either type of therapist behavior, the next segment of participants' speech was most likely to be coded consistent with the prior segment. In fact, simple reflections were even more likely to maintain client ST and CT than were facilitative J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 9 Author Manuscript utterances. For a statistical test of this observation, we cross tabulated simple reflection and facilitative utterances with the outcome that ST, CT or FN was maintained in the subsequent client utterance. Simple reflections were associated with maintaining the client's previous state 56.8% of the time, compared with 43% for facilitative utterances. (P < .0001 accounting for clustering within clients.) Accordingly, we felt it appropriate not to treat these as elicitations, and to use our episode definition as originally conceived. Therefore episodes may include facilitative utterances and/or simple reflections but these elicitation types are ignored in all subsequently described multivariable analyses. 2.6. Multivariable analyses Author Manuscript We used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) logistic regression models (Liang & Zeger, 1986) to estimate Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) for producing CT and ST episodes, respectively, as a function of the various therapist elicitation types (reference = closed question) and selected covariates. The outcome was a repeated binary indicator of CT or ST being produced after an elicitation. Model covariates included prior CT and FN (reference = ST), the early component of the intervention in which ST is intentionally solicited vs. later components, as well as client age, race/ethnicity (dichotomized as white, non-Hispanic vs. all other racial/ethnic groups due to sample characteristics), gender, level of formal education (high school only or more than high school), study site, and therapist. All predictors were included in the GEE models as indicator variables with the exception of client age which was included as a linear term. After fitting the above described main effects models, we added product terms between the prior states and the elicitations to observe whether the relationship between elicitations and subsequent CT and ST episodes was effect modified by prior states. Because there were 15 product terms in these full models and some of them were statistically significant, we chose to simplify interpretation of the findings by fitting main effects models restricted to the sample of episodes that included prior CT, prior ST, or prior FN, respectively, to estimate the AORs for subsequent CT and ST as a function of elicitation type. All GEE models accounted for clustering within participant while specifying an exchangeable working correlation matrix. Author Manuscript 3. Results 3.1. Descriptive data Author Manuscript Of the 132 subjects, 74 (56.1%) were female. Subjects ranged in age from 18 to 60, with a median age of 26. One hundred thirteen (86%) reported White race, 17 Black and 9 Native American including a few reporting multiple race. Forty percent reported having a high school diploma or GED, and 44% at least some college. Forty-one percent were unemployed, and one-third had incomes of less than $10,000/year. Three reported being homosexual, 13 bisexual, and 1 not sure. For the 132 subjects, there were a total of 3450 intervals containing participant CT or ST that did not follow a therapist elicitation (mean 26.1 per encounter). Some of these provided the baseline state for a transition following an elicitation, but we do not otherwise consider them here. There were a total of 17,355 episodes following a therapist elicitation (mean J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 10 Author Manuscript 131). Of these, 9961 (57.4%) consisted of a single MISC-coded client utterance, of which 4302 (43.2%) were CT; 1270 (12.7%) were ST; and 4389 (44.1%) were FN. Of the 7394 (42.6%) episodes containing > 1 MISC-coded utterance, counting only CT and ST, and excluding FN, 2354 consisted of 2 utterances, and 1198 (9.7%) included 3. While the frequency continued to fall with increasing numbers, the distribution had a long tail, with a maximum of 29. (See Fig. 1). Author Manuscript There were a total of 17,232 transitions following a therapist elicitation. (The number of transitions is slightly less than the number of episodes because some elicitations, such as those that began a component of the manualized intervention, did not have a baseline.) Of these elicited episodes with a baseline, 8933 (51.8%) were classified as CT based on the last MISC-coded client utterance; 3325 (19.3%) were classified as ST, and 4974 (28.9%) as FN. In an unadjusted cross tabulation, client ST episodes were followed by ST episodes 42.2% of the time, by CT 34.5%, and by FN 23.3%. Prior client CT was sustained overall 66.9% of the time, followed by FN 21.5%, and by ST in 11.6% of episodes. To allow comparison with some prior studies, we also produced simple three-way crosstabulations of client's prior state of CT or ST, the intervening therapist elicitation (open question, closed question, complex reflections, paraphrasing reflections, summarizing reflections and advise with permission) and the client's succeeding state of CT or ST (i.e., the conventional lag one approach). We compared these results to those obtained using the episode concept and the final utterance. Results were qualitatively similar, but the lag one concept generally resulted in a slightly higher probability of maintaining the client’s prior state. (See Supplemental tables 3 and 4.) Author Manuscript 3.2. Main effects and full models in multivariable analyses Author Manuscript The main effects GEE logistic regression model where CT was the outcome showed that prior CT was indeed the most powerful predictor of subsequent CT (Adjusted Odds Ratio 3.46, 95% confidence interval 3.13–3.86). In addition, open questions, complex reflections, paraphrasing reflection and summarizing reflections were all significantly associated with greater odds of subsequent CT than the reference category of closed questions. Advice with permission was not significantly associated with the odds of CT. In the model where ST was the outcome, prior CT had a strong inverse relationship with subsequent ST (Adjusted Odds Ratio 0.21, 95% confidence interval 0.19–0.024). Open questions, paraphrasing reflections, and summarizing reflections were significantly associated with greater odds of ST, and advice with permission was significantly associated with less odds of ST. Complex reflections were not significantly associated with subsequent ST. (See Supplementary Tables SI and S2 for complete results of the main effects and full model analyses). Table 3 shows the relationship between elicitations and CT given prior CT and ST, respectively; while Table 4 shows the relationship between elicitations and ST given prior CT and ST, respectively. In Table 3, for example, the first column of results shows the total number of each type of elicitation following Participant CT, and the second column shows the number and percent of these which were followed by CT. The Adjusted Odds Ratio for CT compared to the reference category of closed questions, 95% confidence interval, and p- J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 11 Author Manuscript value are shown for all elicitations. In these restricted models, Paraphrasing Reflections and Advice with Permission were not associated with ST transitioning to CT, but Complex Reflections (AOR = 2.69, p < .0001) and Open Questions (AOR = 1.77, p < .0001) were associated with this transition type. Summarizing Reflections were also associated with CT after ST, although this elicitation type was relatively uncommon (AOR = 2.03, p = .0024). All elicitation types excluding Advice with Permission were associated with subsequent CT after prior CT, but Open Questions were the least associated with subsequent CT. Paraphrasing reflections had the strongest association with subsequent change talk after prior CT (AOR = 1.99, p < .0001). Author Manuscript Prior CT was most likely to be followed by ST after Summarizing Reflections (AOR = 1.62, p < .0071), which may reflect that summarizing reflections would have also included reflections of prior participant ST. Open questions were also associated with increased likelihood of ST after CT (AOR = 1.42, p < .0001) compared to closed questions. Again, therapists were instructed to sometimes intentionally elicit ST in the course of the intervention. Advice with permission was the least likely therapist behavior to elicit ST after CT (AOR = 0.26, p ≤0.0001). Prior ST (see Table 4) was most likely to be maintained following paraphrasing reflections (AOR = 1.62, P < .0001). Advice with Permission was associated with less subsequent ST (AOR = 0.25, p = .0012). Other reflections were not associated with maintaining ST. Note that Open Questions are associated with both more CT after ST, and more ST after CT. The latter is because they are associated with less FN, not less CT. Author Manuscript All elicitations other than Advice with Permission were associated with the transition from FN to CT, with Closed Questions as the reference category (Table 5), but only Open Questions and Summarizing Reflections were associated with the transition from FN to ST. 4. Discussion Author Manuscript This study extends the method of sequential analysis of MI technical behaviors in several notable ways. Here, we explored the relationship between specific counselor elicitation techniques and client responses of CT, ST, or FN, while accounting for the client's previous state of motivational expression. We also offer a more comprehensive view of the therapeutic discourse, by incorporating multiple client statements following a therapist elicitation rather than a single or two-lag transition. To do so, we classify the meaning of a given series of motivational statements by how the client's thought is completed. Finally, we consider how client motivation can be influenced via an examination of which therapist behaviors can elicit, for example, a statement in favor of change given a preceding statement against behavior change. Although one must be cautious about causal inference from an observational study such as this, the advantages of sequential analyses have been described as follows: “These transition probabilities, because they preserve the temporal relationship between the process variables, provide stronger support for a causal hypothesis than would be found in a correlational design.” (Moyers et al., 2009; p. 1115). In the present study, results suggest that specific MI J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 12 Author Manuscript techniques function differently in their association with subsequent client statements about change. Specifically, open questions and complex reflections are most likely to be associated with a transition from ST to CT. Open questions are also associated with more ST after CT, which is consistent with correlational relationships reported in recent meta-analyses (Magill et al., 2014; Magill et al., 2018; Pace et al., 2017; Romano et al., 2017). Open questions can have no valence (“Tell me about your drinking”) or can explicitly solicit CT or ST (“Tell me some of the things you like about drinking” vs “What are some of the not so good things about drinking?”). The MI therapist will differentially use these techniques depending on whether the goal is early rapport and engagement or a later focus on motivation for change (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). In fact, the role of the therapist in eliciting, maintaining, or changing the nature of client motivational statements has become of such keen interest to MI process research that the MISC 2.5 now encodes questions and reflections with a subsequent valence (e.g., complex reflection − CT + or CT ‒) (Houck et al., 2010). Author Manuscript The present study provides findings complementary to previous work using the Sequential Code for Process Exchanges (Martin et al., 2005), where valenced elicitations were originally encoded in MI process research. Here, open questions showed similar odds for eliciting CT given ST, and ST given CT. In contrast, complex reflections appeared to preferentially elicit client CT regardless of the prior state, as we also found in the present study. When the prior state was neutral, complex reflections increased the odds for subsequent CT only, while open questions increased the odds of both CT and ST. From these patterns of temporal associations, we suggest that MI therapists effectively use open-ended questioning for both exploration and motivational enhancement, but complex reflections appear to function primarily for motivational enhancement. Author Manuscript Our findings suggest that paraphrasing and simple reflections operate to maintain the status quo. In other words, if momentum in the direction for or against change is the therapist's goal, these interventions may be optimal. This pattern of associations has been found in other sequential analyses, including with other heavy drinking clients recruited in the ED (Houck et al., 2010) and with heavy drinking, mandated, college students (Apodaca et al., 2016). Additionally, the use of simple reflections and paraphrasing may be critical to understanding and clarifying topics being presented by participants. Given the brief nature of these interventions, there is little room for miscommunication and these specific techniques can be used to “check in” and ensure therapists and participants are communicating effectively. Author Manuscript Taken in sum, since the strongest predictor of CT or ST is the previous client state, therapists will want to utilize appropriate techniques either to maintain or change the client's state. Simple and paraphrasing reflections of ST will tend to elicit more ST. (Although we did not explicitly code the valence of these reflections, they almost always have the valence of the preceding client utterance.) Although these reflections are considered MI consistent, if the therapist wishes to move the client from ST to CT, they may be counterproductive. In this situation, open questions are an effective way to achieve the goal of shifting ST to CT. Complex reflections may be particularly effective in shifting ST to CT but they are not always available if the client has not provided the ingredients for them. On the other hand, if J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 13 Author Manuscript the therapist's goal is to maintain CT, then simple and paraphrasing reflections may be relatively more effective. Our results suggest that it may be useful to distinguish among types of reflections in therapist training and evaluation of the technical component of MI. Evaluations of MI fidelity and process may also benefit from a more specific typology than the broad classes of MICO or MIIN behaviors, and these specific indicators are available in several MI coding measures (Houck et al., 2010). Furthermore, while the proposed sub-types of complex reflections were too infrequent to derive probability estimates in relation to CT, ST, or FN, anecdotal, transcript data suggests they may be useful when employed skillfully by the therapist and worthy of future consideration in training and research. See, for example, the following Reflection of Feeling: Author Manuscript P (Referring to the feedback indicating heavy drinking): Because they're lying. I don't really care how they're making me look. That's not my problem. I: I feel like these numbers got you a little upset. I'm feeling a shift a little. P: Maybe a little bit. I drink more than 95%, I think that's funny, but at the same time wow, maybe I should cut down a little bit. Or this example, coded as Agree with a Twist: P: And the legal limit is what? I: 0.08 for driving. P: I don't drive, so I don't have to worry about that. I: You're right, you don't have to worry about the driving part. Author Manuscript P: Smart aleck! I have to worry about the drinking part. 4.1. Limitations and conclusions Author Manuscript The study has several limitations. It is based on a single intervention, with non-treatment seeking participants who were heterogeneous in baseline drinking and sex risk behaviors. Additionally, there were a limited number of therapists across the duration of the study, limiting generalizations. The sample is not very ethnically diverse and results should be generalized with caution. We did not code the valence of complex reflections or open questions, which would have provided more information about the content of these utterances. Prior research has suggested that the valence of questions and reflections is strongly related to subsequent client speech. Furthermore, the validity of our findings depends on our models being correctly specified and that considerable selection bias was not introduced when controlling for prior state. As this study is exploratory, rather than hypothesis-driven, replication is required to draw more confident conclusions. Nevertheless these results have strong face validity and can readily be tested both by subsequent observational studies and possibly through experimentation. The more complex operationalization of CT and ST to account for multiple client utterances following an elicitation also has face validity and may result in more specific and valid evaluation of the technical hypothesis of MI. It suggests that simply counting the frequency of MICO and J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 14 Author Manuscript MIIN behaviors, and the frequency of CT and ST over the course of a session is an inadequate representation of the technical component of MI, and that conflating complex, simple and paraphrasing reflections is misleading. It may be profitable to train therapists in the specific uses of these techniques over the course of an MI session. Supplementary Material Refer to Web version on PubMed Central for supplementary material. Acknowledgments Funding sources This work was supported by grants U24 AA022003, K05 AA019681, PO1 AA019072, and R01 AA09892 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Author Manuscript References Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Apodaca TR, Jackson KM, Borsari B, Magill M, Longabaugh R, Mastroleo NR, & Barnett NP (2016). Which individual therapist behaviors elicit client change talk and sustain talk in motivational interviewing? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 61, 60–65. [PubMed: 26547412] Apodaca TR, & Longabaugh R (2009). Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction, 104(5), 705–715 [PubMed: 19413785] Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Frarikforter TL, Van Horn D, Crits-Christoph P, … National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials, N (2007). Site matters: Multisite randomized trial of motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 556–567. [PubMed: 17663610] Chicchetti V (1994). Guidelines, criteria and rules of thumb for evluated normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290. Cohen J (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. D’Amico EJ, Houck JM, Hunter SB, Miles JN, Osilla KC, & Ewing BA (2015). Group motivational interviewing for adolescents: Change talk and alcohol and marijuana outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(1), 68–80. [PubMed: 25365779] Gaume J, Bertholet N, Faouzi M, Gmel G, & Daeppen JB. (2010). Counselor motivational interviewing skills and young adult change talk articulation during brief motivational interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39(3), 272–281. [PubMed: 20708900] Hettema J, Steele J, & Miller WR (2005). Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 91–111. Houck JM, & Moyers TB (2015). Within-session communication patterns predict alcohol treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 205–209. [PubMed: 26573732] Houck JM, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Glynn LH, & Hallgren K (2010). In University of New Mexico (Ed.). Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) Version 2.5. S. A. a. A. Center on Alcoholism. Kahler CW, Caswell AJ, Laws MB, Walthers J, Magill M, Mastroleo NR, … Monti PM (2016). Using topic coding to understand the nature of change language in a motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and sex risk behaviors in emergency department patients. Patient Education and Counseling 99(10), 1595–1602. [PubMed: 27161165] Laws MB, Beach MC, Lee Y, Rogers WH, Saha S, Korthuis PT, … Wilson IB. (2013). Providerpatient adherence dialogue in HIV care: Results of a multisite study. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 148–159. [PubMed: 22290609] J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 15 Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Laws MB, Lee Y, Rogers WH, Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, … Wilson IB. (2014). Providerpatient communication about adherence to anti-retroviral regimens differs by patient race and ethnicity. AIDS and Behavior, 18(7), 1279–1287. [PubMed: 24464408] Liang K-Y, & Zeger SL (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73(1), 13–22. Lindqvist H, Forsberg L, Enebrink P, Andersson G, & Rosendahl I (2017). The relationship between counselors' technical skills, clients' in-session verbal responses, and outcome in smoking cessation treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 77, 141–149. [PubMed: 28245946] Lundahl B, & Burke BL. (2009). The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: A practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(11), 1232– 1245. [PubMed: 19739205] Magill M, Apodaca TR, Borsari B, Gaume J, Hoadley A, Gordon REF, … Moyers T. (2018). A metaanalysis of motivational interviewing process: Technical, relational, and conditional process models of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(2), 140–157. [PubMed: 29265832] Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, & Longabaugh R (2014). The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of MI's key causal model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 973–983. [PubMed: 24841862] Martin T, Moyers TB, Houck JM, Paulette C, & Miller WR (2005). Motivational Interviewing Sequential Code for Observing Process Exchanges (MI-SCOPE) coder's manual U. o. N. Mexico. Miller WR, Moyers TB, Ernst D, & Amrhein PC (2003). Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC). Albuquerque: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions, University of New Mexico. Miller WR, & Rollnick S (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press. Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2012). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd ed.). New York, New York: The Guilford Press. Miller WR, & Rose GS (2009). Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. The American Psychologist, 64(6), 527–537. [PubMed: 19739882] Miller WR, Yahne CE, & Tonigan JS (2003). Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: A randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 754–763. [PubMed: 12924680] Monti PM, Mastroleo NR, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Kahler CW, & Operario D. (2016). Brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and HIV/sexual risk behavior in emergency department patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(7), 580–591. [PubMed: 26985726] Moyers TB, Martin T, Christopher PJ, Houck JM, Tonigan JS, & Amrhein PC (2007). Client language as a mediator of motivational interviewing efficacy: Where is the evidence? Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(10 Suppl), 40s–47s. Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, & Tonigan JS. (2009). From insession behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1113–1124. [PubMed: 19968387] Moyers TB, Miller WR, & Hendrickson SM. (2005). How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 590–598. [PubMed: 16173846] Pace BT, Dembe A, Soma CS, Baldwin SA, Atkins DC, & Imel ZE (2017). A multivariate metaanalysis of motivational interviewing process and outcome. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(5), 524–533. [PubMed: 28639815] Romano M, Arambasic J, & Peters L. (2017). Therapist and client interactions in motivational interviewing for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(7), 829–847. [PubMed: 27797402] Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [PubMed: 8329970] J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 16 Author Manuscript Winhusen T, Kropp F, Babcock D, Hague D, Erickson SJ, Renz C, … Somoza E. (2008). Motivational enhancement therapy to improve treatment utilization and outcome in pregnant substance users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35(2), 161–173. [PubMed: 18083322] Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 17 Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Fig. 1. Number of elicited episodes by episode length. (The right tail is not visible. Maximum MISC-coded utterance count in an episode is 29.) Author Manuscript Author Manuscript J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 18 Table 1 Author Manuscript Elicitation concepts. Label Definition Example Closed Question (Reference Category) Questions that require a brief-specific answersuch as yes or no-a choice of limited optionsor simply to specify a number-a color-date-or time-etc. Have you thought about completely stopping? Open Question A broad question without limited response categories-i.e. cannot be answered by “yes/no” or a limited list of choices. What are some of the good things about alcohol? Paraphrasing Reflection The therapist reflects what the client says but infers additional meaning to test a hypothesis about the speaker's inner state and encourage further elaboration P: Drinking makes it so much easier for me to talk to new people. I: You're more social and less nervous around new people when you drink. Complex Reflections (Combined into one category for this analysis) Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Double-sided Reflection A type of paraphrasing which reflects both sides of ambivalence asserted by client. On the one hand drinking with your friends seems to make it easier to talk to new people – and on the other hand after a night of drinking you wake up tired and hung over-which is something you don't like feeling. Metaphorical Reflection Speaker replaces a word or phrase in a client’s assertion with a figure of speech or image suggesting an analogy P: I really want to go out and be with my friends but all they ever do is drink-and I don't want to be around that. I: You're really stuck between a rock and a hard place. Reflection of Feeling Therapist emphasizes emotional content of client's assertion-perhaps inferring unstated emotion from body language-tone of voice-or deduction. P: I'm constantly being woken up by drunk students. I: You're angry with the students who disturb your sleep. Reframing Acknowledge validity of client's assertion but offer an encouraging reinterpretation. P: I have tried so many times and failed. I: You're very persistent-the change must be important to you. Agree with Twist Similar to reframing but with a more substantive reinterpretation. Begins with agreement-changes direction to encourage goal attainment. P: I have started walking to class-but I can't seem to get myself to the gym to work out. I: You recognize exercise is important-you are putting a lot of effort to being more active. Amplified Reflection Therapist exaggerates or restates client assertion in a less credible way-to prompt reevaluation. P: My girlfriend nags me go to the gym and work out. I: it seems to you that she has no reason for concern. Summarizing Reflection (Often serves to end a segment and move on; not necessarily functioning as an elicitation) Therapist pulls together highlights of complex story told by interlocutor-perhaps over several preceding turns-in a succinct restatement. I: So it sounds like for you-you like sex to be spontaneous. You enjoy sex-and there's certain expectations you have on how it should go. But when you don't use a condom-it causes you a lot of worry-anxiety. But on the other hand-there are times when you don't use a condom-just because you're spontaneous-or you feel like you know the person. Author Manuscript J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Laws et al. Page 19 Table 2 Author Manuscript Transition frequencies and probabilities for client speech based on intervening counselor facilitative utterances and simple reflections. Participant prior speech/ counselor speech Participant response Total Author Manuscript ST: n (p) CT n (p) FN n (p) N Prior ST/Simple Reflection 157 (.534) 77 (.262) 60 (.204) 294 Prior CT/Simple Reflection 83 (.109) 541 (.718) 137 (.180) 761 Prior FN/Simple Reflection 67 (.154 115 (.264) 254 (.583) 436 Prior ST/Facilitative Utterance 651 (.441) 404 (.274) 420 (.285) 1475 Prior CT/Facilitative Utterance 399 (.138) 1816 (.628) 677 (.234) 2892 Prior FN/Facilitative Utterance 274 (.175) 502 (.320) 793 (.505) 1569 ST = Sustain Talk; CT = Change Talk; FN = Follow Neutral. Author Manuscript Author Manuscript J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript 3601 256 358 2090 Paraphrase Summarize Advice with Permission Closed Question 1237 (59.2) 200 (55.9) 186 (72.6) 2637 (73.2) 206 (72.3) 1480 (64.4) REF 0.83 1.92 1.99 1.82 1.26 REF 0.65–1.04 1.46–2.51 1.73–2.29 1.42–2.34 1.09–1.46 REF 0.11 < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01 p 728 48 96 1525 132 856 212 (29.1) 19 (39.6) 41 (42.7) 462 (30.3) 69 (52.3) 364 (42.5) N of CT following elicitation (%) REF 1.38 2.03 1.08 2.69 1.77 AOR REF 0.71–2.66 1.30–3.22 0.85–1.36 1.80–4.02 1.38–2.25 95% CI REF 0.35 < 0.01 0.52 < 0.01 < 0.01 p Note: Models statistically adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, gender, education, study site, and therapist. CT = Change Talk. AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. Ref = Reference Category. 285 2299 Complex Reflection Open Question 95% CI N of elicitations following ST AOR N of elicitations following CT N of CT following elicitation (%) Restricted to prior sustain talk Restricted to prior change talk GEE models to interpret effect modification when change talk is the outcome. Author Manuscript Table 3 Laws et al. Page 20 J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript 3601 256 358 2090 Paraphrase Summarize Advice with Permission Closed Question 236 (11.3) 10 (2.8) 44 (17.2) 356 (9.9) 37 (13.0) 347 (15.1) REF 0.26 1.62 0.87 1.21 1.42 REF 0.15–0.45 1.14–2.29 0.71–1.07 0.88–1.65 1.20–1.68 REF < 0.01 0.01 0.19 0.25 < 0.01 p 728 48 96 1525 132 856 274 (37.6) 6 (12.5) 34 (35.4) 751 (49.3) 47 (35.6) 318 (37.2) N of ST following elicitation (%) REF 0.25 0.87 1.62 0.91 0.97 AOR REF 0.10–0.58 0.54–1.42 1.31–1.99 0.61–1.36 0.79–1.19 95% CI REF < 0.01 0.58 < 0.01 0.66 0.77 p Note: Models statistically adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, gender, education, study site, and therapist. ST = Sustain Talk. AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. REF = Reference Category. 285 2299 Complex Reflection Open Question 95% CI N of elicitations following ST AOR N of elicitations following CT N of ST following elicitations (%) Restricted to prior sustain talk Restricted to prior change talk GEE models to interpret effect modification when sustain talk is the outcome. Author Manuscript Table 4 Laws et al. Page 21 J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22. Author Manuscript Author Manuscript 1779 146 139 1368 Paraphrase Summarize Advice with Permission Closed Question 389 (28.4) 49 (35.3) 69 (47.3) 655 (38.8) 67 (51.2) 591 (42.4) REF 1.21 2.23 1.55 2.61 1.86 REF 0.84–1.73 1.48–3.39 1.35–1.80 1.82–3.78 1.55–2.23 REF 0.30 < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01 1368 193 146 1779 131 1395 206 (15.1) 139 (4.3) 44 (30.1) 266 (15.0) 16 (12.2) 327 (23.4) N of ST following elicitation (%) REF 0.27 2.44 0.99 0.83 1.73 AOR REF 0.11–0.68 1.51–3.56 0.83–1.20 0.51–1.32 1.43–2.12 95% CI Note: Models statistically adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, gender, education, study site, and therapist. ST = Sustain Talk. AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. REF = Reference category. 131 1395 Complex Reflection Open Question p N of elicitations following FN 95% CI N of elicitations following FN N of CT following elicitation (%) Restricted to prior neutral to predict sustain talk Restricted to prior neutral to predict change talk AOR Author Manuscript GEE models to interpret effect modification restricted to prior neutral. REF 0.01 < 0.01 0.95 0.43 < 0.01 p Author Manuscript Table 5 Laws et al. Page 22 J Subst Abuse Treat. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 November 22.