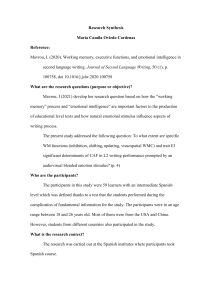

Academy of Management Learning & Education R er Pe Impact and University Business Training Courses Delivered to the Marginalized: A Systematic Review ie ev Journal: Academy of Management Learning & Education Manuscript ID AMLE-2021-0244-SISI.R3 Manuscript Type: Special Issue on Scholarly Impact w Pr Course design, Cross-cultural issues in management education, ESubmission Keywords: learning, Management education, Outcome assessment, Diversity and management education f- oo Scholars, practitioners, policymakers, and accreditors challenge business schools to extend their impact beyond academia and into the real world. Many management academics have responded by becoming involved in business training programs that seek to improve the well-being of marginalized individuals. However, work that conceptualizes and measures the efficacy of these activities has not been systematically analyzed. In this article, we provide the first review. We find that the research is dominated by examinations of short-term, individual-level Abstract: outcomes, such as securing employment. Yet little is written about the impact of business training programs (especially over time) at either a collective or system level. We use our review to argue for theoreticallyinformed approaches to redress this gap, highlighting underemphasized directions for future research. We also provide recommendations to assist program design, noting that good practice involves hybrid models of education that build capacity within marginalized communities. Further, program designs ought to support broader social goals, such as helping these communities to thrive. n sio er lV ina tF No Page 1 of 42 Impact and University Business Training Courses Delivered to the Marginalized: A Systematic Review R er Pe Tracey Dodd University of Adelaide [email protected] w ie ev Chris Graves University of Adelaide Pr [email protected] f- oo Janin Hentzen No [email protected] Acknowledgments er lV ina tF The authors thank Professors Tyrone Pitsis and Usha Haley and the three anonymous n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education reviewers for their excellent guidance and support throughout the development of the manuscript. Academy of Management Learning & Education Impact and University Business Training Courses Delivered to the R er Pe Marginalized: A Systematic Review Abstract Scholars, practitioners, policymakers, and accreditors challenge business schools to extend ie ev their impact beyond academia and into the real world. Many management academics have responded by becoming involved in business training programs that seek to improve the w well-being of marginalized individuals. However, work that conceptualizes and measures the efficacy of these activities has not been systematically analyzed. In this article, we Pr provide the first review. We find that the research is dominated by examinations of short- oo term, individual-level outcomes, such as securing employment. Yet little is written about f- the impact of business training programs (especially over time) at either a collective or system level. We use our review to argue for theoretically-informed approaches to redress No this gap, highlighting underemphasized directions for future research. We also provide tF recommendations to assist program design, noting that good practice involves hybrid models of education that build capacity within marginalized communities. Further, lV ina program designs ought to support broader social goals, such as helping these communities to thrive. n sio er 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 2 of 42 Academy of Management Learning & Education Page 3 of 42 INTRODUCTION Scholars, policymakers, accreditors, and others have argued that management education R er Pe can play a critical role in economic and social development (Spicer, Jaser, & Wiertz, 2021). To this end, many business schools are making a concerted effort to offer management training to marginalized individuals – the idea being that learning these skills will work to ie ev the betterment of the marginalized person’s well-being while helping to redress significant social problems. Examples of these programs abound, including at some of the QS Worldranked universities. For instance, there is the University of Toronto’s Rise Asset w Development program, which aims to increase self-efficacy among vulnerable populations Pr between the age of 16 to 29. There is also New York University’s Veterans oo Entrepreneurship Training program, which aims to upskill military personnel, veterans, and their spouses who wish to pursue business ventures. However, there is no consensus f- on whether such offerings are, in fact, effective (Fayolle, 2013; Productivity Commission, No 2019). Indeed, defining and measuring the impact of such programs could be highly contested due to the many tensions and trade-offs that emerge between individual short- tF term outcomes, such as employment, and longer-term impacts such as overall well-being at a social and collective level. lV ina We thus seek to advance understanding of these issues by critically analyzing peerreviewed studies on how society can reduce marginalization through university business er training courses. Three questions are answered in the process: (i) How do scholars n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 conceptualize and evaluate the outcomes and associated impact of business training delivered to marginalized individuals?; (ii) What is the current state of knowledge regarding the theory of change and pedagogy of these programs, including the relationships Page 4 of 42 Academy of Management Learning & Education between program design, outcomes, and impact?; and (iii) How can future research and practice be improved? R er Pe These questions are answered through a problematizing review (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2020). Before outlining the review method, findings, and discussion on the implications for the domain of scholarly impact, we first provide further detail of the research context. ie ev RESEARCH CONTEXT Business schools face pressure to engage with the real world in more meaningful ways w (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, AACSB, 2022; Kitchener & Pr Delbridge, 2020). Yet methods for assessing the impact these efforts are having are lacking (MacIntosh, Beech, Bartunek, Mason, Cooke, & Denyer, 2017). The most used metrics oo include research publications, citation counts (Aguinis, Shapiro, Antonacopoulou, & f- Cummings, 2014), and journal rankings (Özbilgin, 2009). But these shed little light on the broader definition of impact – meaning change – either at a system or an individual level No (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021). Haley, tF Cooper, Hoffman, Pitsis, & Greenberg (2020) warn that this knowledge gap threatens the future legitimacy of business schools and management education research (also see Haley, Page, Pitsis, Rivas, & Yu, 2017). lV ina More specifically, there is a dearth of insight regarding the impact of university-based er training programs for the marginalized (i.e., people who are underrepresented in the higher education system) (Sitzmann & Wienhardt, 2019). This includes non-degree awarding n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 programs, short courses, and other micro-credentials delivered either by or in partnership with a higher education institution (Wang, 2020). Training interventions offer a site of direct interaction and impact (Kirkpatrick, 1976; 1994; MacIntosh et al., 2017). However, Page 5 of 42 recent efforts to conceptualize and advance understanding of impact in the context of teaching (e.g., Ford, 2021) do not comprehensively consider the marginalized. R er Pe Addressing this omission is timely. As stated earlier, universities engage with marginalized cohorts to reduce inequality through such programs. These endeavors are based on the prevailing view that further education will reduce poverty and increase well-being ie ev (Chakravarty, Lundberg, Nikolov, & Zenker, 2019) – views that are supported by policymakers and others (AACSB, 2022; OECD, 2020; Salmi, 2020). Yet while these w efforts align with calls to reform business schools for the betterment of social goals (Kitchener & Delbridge, 2020), if there is no proper gauge as to the impact of these Pr programs, society cannot know if such actions are indeed effective and whether said oo training programs are achieving optimal results. f- Knowledge of whether (and how) training can address the structural issues that cause marginalization, such as systemic racism or excessive economic and social inequality, is No nascent (Piketty, 2020; Prieto, Phipps, Stott, & Giugni, 2021). Marginalized individuals tF are not homogeneous (Sitzmann & Campbell, 2021) and business methodologies and ways of seeing the world are not necessarily compatible with different knowledge systems, lV ina approaches, and cultures (Doucette, Gladstone, & Carter, 2021; Simpson, 2006). While training for the marginalized can sometimes increase employment (Fayolle, 2013), wealth (Fairlie & Krashinsky, 2012), and self-determination (Scott, Dolan, Johnstone-Lois, er Sugden, & Wu, 2012), many unintended consequences can also emerge. For example, n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education training programs may entrench existing bias in the community, such as relegating the marginalized to entry-level employment positions (Girei, 2017). Increased employment, wealth, and economic growth can also place additional pressure on natural systems, as Page 6 of 42 Academy of Management Learning & Education currently witnessed in the climate crisis (Hickel, 2021). Hence, while scholars have shown that business training must balance the tension between individual liberty and R er Pe social/collective welfare, gaps in our knowledge of how to do this remain (Prieto et al., 2021). Additionally, further studies are required to unpack and resolve the counterproductive assumptions that might underpin such training programs, like the ie ev assumption that participants have access to the resources required to complete the program (e.g., internet access, time, financial capacity, etc.) or that the needs of marginalized are homogeneous. That said, defining impact in a way that all agree on could be a highly w contested task. It could certainly be classified as a wicked problem and may even be Pr impossible to solve (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Taking a more optimistic approach, we would oo prefer to frame the task as a “grand challenge” (Spicer et al., 2021). This is because grand challenges, while complex, are solvable if the stakeholders who are impacted (or who can f- impact the problem) harness their expertise and knowledge. To this end, we undertook a No review of peer-reviewed research to uncover and problematize these tensions and tradeoffs and chart ways forward. lV ina METHOD tF Our review spanned Web of Science and Scopus (Paul & Criado, 2020) and employed a range of search terms used in the literature regarding marginalization and relevant training programs (see Appendix 1).1 We selected peer-reviewed journals as they adhere to er scholarly standards, including transparent data collection and reflexivity, which examine n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 underlying the tensions and trade-offs that emerge in our setting. Additionally, unlike grey 1 Articles relating specifically to the completion of university degrees or post-graduate (i.e., award) programs were excluded, as these have been covered elsewhere (e.g., Rodríguez-Hernández, Cascallar & Knydt, 2020). Page 7 of 42 material, such as peer-reviewed conference papers and grant reports, which are not publicly available, peer-reviewed journals are readily available and can be accessed by anyone R er Pe wishing to analyze them. We limited the search to English articles and excluded books, book chapters, non-peer-reviewed articles, and conference papers.2 As shown in Appendix 1, we filtered the search results down to a final corpus of 43. This ie ev review process involved all authors analyzing the titles and abstracts of relevant papers and excluding articles that did not reference business-related training. Team consensus was w sought to decide and determine whether the article met our inclusion criteria of involving a non-degree awarding university training program that included business content Pr delivered to marginalized groups or individuals. We recognize that a small sample frame oo could be viewed as a limitation of our review and highlight that, consistent with Bacq, f- Drover, and Kim (2021, p. 2), small sample frames (e.g., “21–30 articles”) are indeed appropriate when scholars seek to provide deep analysis to problematize and advance a No field of research (also see Alvesson & Sandberg, 2020). tF Selected articles were uploaded into NVivo12 and coded. All authors helped with the coding, coming together as a team to discuss and agree on the final coding scheme using lV ina abductive logic. Abductive coding involves analyzing data to identify how emerging themes are similar or different from existing research. Three levels of coding were employed: first-order codes, second-order themes, and third-order concepts. n sio er 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education 2 At the suggestion of an anonymous reviewer, we did look at books and book chapters. While we identified 11 books and book chapters, none of these met our inclusion criteria. Thus, we retained our original search strategy. Page 8 of 42 Academy of Management Learning & Education In refining labels for second-order themes, we noted that many of the first-order codes listed in Appendix 2 were consistent with the integral pheno-practice of well-being (IPW) R er Pe framework, specifically the version put forward by Painter-Morland, Demuijnck, & Ornati (2017). The IPW framework considers four levels of influence: individual-objective outcomes (e.g., employment attainment), intra-subjective outcomes (e.g., improved life ie ev satisfaction), collective impacts (e.g., social capital), and system-level impacts (e.g., improved governance). The IPW framework allows scholars to consider how people interact within systems. For example, does positive change at the micro-level (e.g., for one w group of marginalized people) result in meso-level change across a community (e.g., Pr increased social capital and cohesion), or does it result in conflict and new tensions such oo as increased competition for resources? Further, how do changes at the micro and mesolevels influence macro-change at a social level? Does the tide rise evenly through improved f- community governance and respect for nature or do social and environmental systems No suffer as individuals and communities change? This view is critical as work examined within our review (e.g., Halkic & Arnold, 2019; Prieto et al., 2021) and beyond (e.g., Bhatt, tF Qureshi, & Sutter, 2022) show that social interventions designed to reduce marginalization lV ina can (re)produce rather than reduce social inequalities. What is highlighted is that dominant groups and classes may emerge; thus positive change at the individual level for one marginalized group cannot guarantee a collective positive impact across other marginalized groups (Bhatt et al., 2022). n sio er 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Further, there is an increasing acceptance in the literature of the need to consider subjective and non-monetary impact variables (Painter-Morland et al., 2017). As such, our codebook (Appendix 2) and emerging framework provided us with a conceptual contribution that let Academy of Management Learning & Education Page 9 of 42 us examine the tensions and trade-offs in the literature. The IPW framework conceptualizes impact in a way that moves away from “rational calculative decision-making” to entertain R er Pe alternative frames and different world views, along with intergenerational impacts – perspectives that one does not see in short-term, individual-oriented evaluations (PainterMorland et al., 2017, p. 296). While we did not commence our review with a specific ie ev framework in mind, through reflexive analysis, the IPW framework emerged as an appropriate organizing framework for us to label second-order themes. The IPW framework also urges scholars to consider the temporal implications of change, mapping w how results at the individual level result in collective and social impact. Thus, and as shown Pr in Figure 1, first-order codes that considered individual-objective outcomes were assigned oo to a second-order theme of “behavioral and cognitive outcomes.” Intra-subjective outcomes were coded as “consciousness,” inter-subjective (group level) impacts were f- coded as “collective social,” and broader impacts, such as improved governance, were No coded as “system” (inter-objective). These second-order themes are consistent with the conceptualization of “outcomes” and “impact” as used within the broader evaluation literature (Newcomer, Hatry, & Wholey, 2015). lV ina tF -----------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here ------------------------------------ As the IPW framework does not consider the design of training programs, we sought out er additional education evaluation frameworks to refine other codes. Through this process, n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 we found that codes relating to program design aligned neatly with the integrated teaching model (Nabi, Liñán, Fayolle, Krueger, & Walmsley, 2017). Hence, programs using simple reproduction methods as their teaching models, such as lectures, readings, and exercises (Chen, Davis, Krause, Aivaloglou, Hauff, & Houben, 2018), were coded as “supply-based Page 10 of 42 Academy of Management Learning & Education approaches” (Nabi et al., 2017). Programs whose pedagogy involves regular classes, guest speakers, building student networks, and one-on-one mentoring (Taylor, Jones, & Boles, R er Pe 2004) were coded as “demand-based approaches” (Nabi et al., 2017). Programs that incorporate action methods for teaching where students apply what they have learned in a real-world setting and receive feedback on the competencies they have learned (Alaref, ie ev Brodmann, & Premand, 2020) were coded as “competency-based approaches” (Nabi et al., 2017). Programs involving a combination of these pedagogical approaches were coded as “hybrid” (Nabi et al., 2017). w Pr We also used the integrated teaching model to finalize the first-order codes for the research methods used in empirical studies. Articles that included current and ongoing measures oo during the program (e.g., course grades) were coded as Level 1. Articles that included pre- f- and post-program measures (e.g., course completion and leadership capabilities) were coded as Level 2. Articles that included measures between 0 and 5 years post-program No (e.g., the number and type of start-ups, increases in business performance, etc.) were coded tF as Level 3. And articles that included measures 3 to 10 years post-program (e.g., the survival of start-ups) were coded as Level 4. Interestingly, Nabi et al. (2017, p. 279) discuss lV ina a code for Level 5 articles, which measure impact 10+ years post-program, including contributions to society and the economy. However, none of the studies in our results included data past 10 years. er The final data structures relevant to program design also included second-order themes n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 related to the “theory of change” and “forms of marginalization” (see Appendix 2). In terms of the theory of change, we coded for the explicit theory used in the article as well as implicit assumptions, such as the assumed needs of the marginalized that informed the Academy of Management Learning & Education Page 11 of 42 program design. Regarding forms of marginalization, four first-order codes emerged: disadvantaged (persons with disabilities and/or low literacy and socioeconomic status); R er Pe underrepresented (gender, ethnicity, Indigenous); developing nation; and unemployed. When a study addressed two forms of marginalization, we listed it under the most prominent first-order code. ie ev Thus, ultimately, while our organizing framework draws on the problematizing approach (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2020), it is also consistent with structured approaches to reviews, w such as the Theory, Construct, Characteristics, and Methodology (TCCM) approach. TCCM uses literal coding to identify trends and patterns in the data (Paul & Criado, 2020). Pr We combined abductive and literal coding to provide a transparent and structured coding oo process that can be reproduced. This hybrid approach overcomes the limitations of f- structured approaches as stand-alone methods which Alvesson and Sandberg (2020) caution may not encourage authors to dig deeper into the meanings behind and limitations of existing work. tF No FINDINGS lV ina To provide context for the core contributions identified, this section begins with an overview of the articles in our review. Characteristics of the Studies er Our data consists of 43 articles published predominantly in education (47%) and n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 management journals (17%) from 1980 to 2021, with around 40% published in the past five years. Outside of education and management, articles were also published in journals concerned with entrepreneurship, economics, information systems, sociology, and social Academy of Management Learning & Education work. Additionally, several journals were multidisciplinary. Thirty-eight articles were empirical, with the remaining five being conceptual (Table 1). Most articles primarily R er Pe focused on programs delivered to the disadvantaged (e.g., socially excluded due to a disability, low literacy, or low socioeconomic status) (37%), underrepresented groups (e.g., gender or ethnicity) (35%), people who are unemployed (14%), and developing nations ie ev (14%). The contexts covered included country-specific programs (85%) and cross-national studies (15%), with most articles relating to the United States (35%), followed by African countries (26%). Common training programs included entrepreneurial training (42%), w multidisciplinary training (19%), professional development (9%), leadership (7%), and economics (7%). oo Pr Turning to our findings, Table 1 provides a summary. f- -----------------------------------Table 1 about here ------------------------------------ tF No Conceptualization, Measurement, and Achievement of Outcomes The body of work examined suggests that individual behavioral outcomes, cognitive lV ina outcomes, and consciousness outcomes are pertinent to programs, with individual behavioral and cognitive outcomes being the dominant focus. All articles considered individual behavioral and cognitive outcomes, while just over half (58%) provided insight er into consciousness outcomes. Commonly listed individual behavioral and cognitive n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 12 of 42 outcomes included the development of capabilities (e.g., acquiring communication skills, building up knowledge skills, and business literacy) (91%), educational attainment (51%), Page 13 of 42 and employment (42%). The consciousness outcomes considered included improved choice (33%), perceived freedom (28%), identity (26%), and life satisfaction (7%). R er Pe Interestingly, our results show that educators misestimate the potential outcomes that can be achieved when designing and delivering business training programs. Of the 38 empirical articles, 68% reported that the training programs had achieved their intended individual ie ev behavioral and cognitive outcomes, while 42% reported that the programs achieved their intended consciousness outcomes. Eight percent additionally reported individual-objective w outcomes greater than intended (Anosike, 2018; Bulger, Bright, & Cobo, 2015; Majee, Long, & Smith, 2012), but none reported consciousness outcomes greater than intended. Pr Conversely, 16% reported individual behavioral and cognitive outcomes less than that oo intended (Co & Mitchell, 2006; Dillahunt, Wang, & Teasley, 2014; Macleod, Haywood, f- Woodgate, & Alkhatnai, 2015), and 5% reported consciousness outcomes less than intended. Some noteworthy examples include a community leadership program evaluated No by Majee et al. (2012), which achieved the unintended outcome of improved employability tF in addition to the intended outcome of developing leadership capabilities. This program “had a ripple effect of opening ‘wider doors’ for program graduates” and, consequently job lV ina opportunities (Majee et al., 2012, p. 91). Further, it seems that empirical work may overemphasize individual behavioral and cognitive outcomes, resulting in lower evidence of subjective outcomes. For example, Riebe (2012) and Halkic and Arnold (2019) suggest er that programs can increase autonomy and perceived freedom among the marginalized, n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education including females and refugees, yet the authors provide no empirical support. However, the above results regarding efficacy (or lack thereof) require us to consider research rigor. Our analysis of the empirical studies suggests that whether training Academy of Management Learning & Education programs report achieving or exceeding their intended outcomes may be partially influenced by the data collection methods used. For example, Riebe (2012) evaluates a R er Pe university-based training program evaluated for women entrepreneurs. The intended outcomes of the program included employment, perceived autonomy, and freedom of choice, but it was unclear whether these objectives were achieved. In fact, close to a quarter ie ev of the empirical studies (24%) did not identify the data collection methods used, and some did not report on whether the program’s intended outcomes were achieved. Further, while many authors identify the potential for training programs to contribute to outcomes, few w consider incorporating these outcomes into the design and evaluation of their programs. Pr For example, Halkic and Arnold (2019) articulate how the MOOC model can further oo educational choices for refugees, but they do not evaluate this type of outcome in their study. As another example, Anosike (2019) finds that entrepreneurship education is f- effective for improving the capabilities and employment prospects of youth in conflict-torn No northern Nigeria. But the finding is based on only a small cohort of ten interviewed participants, and it does not include a longitudinal analysis to ascertain whether the tF employment outcomes were sustained. Alaref et al. (2020), who did employ a longitudinal lV ina analysis to study the same type of program, found that outcomes such as capabilities and employment prospects were not sustained over time. More specifically, these authors saw improvements one year post-program, but by four years these positive effects had er evaporated. This suggests some outcomes may be time-sensitive, which is a concern given n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 14 of 42 that nearly half (45%) of these empirical studies use data collected only during the program. Conceptualization, Measurement, and Achievement of Impact Page 15 of 42 Regarding impacts, we find that collective social and system impacts are salient, with greater attention paid to collective social impacts. 72% of the articles considered collective R er Pe social impacts, while 53% considered system impacts. Social cohesion (28%), social relationships (26%), stable professional partnerships (26%), and developing social capital—including expanded social networks (23%) and overcoming or avoiding ie ev loneliness (5%)—were the most commonly-mentioned collective social impacts. System impacts included community benefits (40%), community resources (26%), and good governance (14%). w In relation to efficacy, 29% of the empirical papers report their training programs achieved Pr the intended system impacts, 26% report collective social impacts being achieved, and 13% oo report positive unintended collective social impacts. Notably, Wang (2020) highlights that f- training programs for the marginalized are efforts to improve social equity and observes that they provide a domain for the higher education system to create an improved social No contract with the community. Halkic and Arnold (2019, p. 361) add that this is a “complex tF endeavor” that required business schools to address barriers to participation (e.g., access to the internet and financial support). However, as with the outcomes, many authors did not lV ina engage in this reflective practice. For example, Habel and Whitman (2016, p. 82) state that: “Universities need to adopt more sophisticated approaches to evaluating access and enabling programs rather than simply focusing on quantitative outcomes of throughput and er grade point averages.” Yet, the authors themselves do not reflect on the measures employed n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education in their study to consider impact. 11 of the 38 empirical papers conceptualize collective social impacts without empirically examining them, and 6 for system impacts. For example, Anosike (2019) discusses how entrepreneurship education could help to develop Academy of Management Learning & Education human capital and consequently reduce youth unemployment and vulnerability, but provides no evidence of these potential impacts. This suggests that although many authors R er Pe identify the potential for training programs to achieve impact, considering and incorporating them into the design and scholarly evaluation of programs is nascent. Potential Insight into How and Why Programs Contribute to Positive Outcomes and ie ev Impact: Pedagogy In relation to how and why programs contribute to positive outcomes and impact, we found w emerging themes relating to program design. Theory was explicitly used and implicit Pr assumptions were made that informed the types of training offered to different marginalized groups. f- Explicit theory of change oo We found explicit theories of change were used to explain how pedagogy was selected and No evaluated in around three-quarters of the studies. This included social capital theory (Jackson, Colvin, & Bullock, 2020; Taylor et al., 2004), entrepreneurship theory (Anosike tF 2018, 2019), self-regulated learning theory (Archibald, Muhammad, & Estreet, 2016; Chen lV ina et al., 2018), the theory of planned behavior (Karimi, Biemans, Lans, Chizari, & Mulder, 2016), and learning theory (Bulger et al., 2015). However, the scholarly application of these theories was underdeveloped and rarely used to provide deep insights into impact. er For example, Hinson and Amidu (2006) examine internet adoption in Ghana and whether n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 16 of 42 training had increased the participants’ skills in information seeking. Yet, the authors draw on the “Internet Benefit Model” (Hinson & Amidu, 2006, p. 315) to support their results and do not consider any of the broader impacts that these capabilities may influence— Page 17 of 42 despite arguing that one of the main reasons for building participant internet skills was to access online resources to benefit the community. Ideally, the authors would have used this R er Pe opportunity to reflect on the overall program design and the program’s impact; however, we found the need for further work. Few scholars took an abductive and reflexive perspective. For example, most authors treat ie ev training as a well-defined solution to problems facing the marginalized (e.g., unemployment). Analysis in these papers is limited and focuses on the correct implementation of training programs in ways that assist the marginalized to adapt to w existing social norms. For example, Mishra (2014) examines how a program introduces Pr “hygiene, sanitation, and routine discipline[s]” to assist the marginalized in fitting existing oo cultural workplace expectations. In contrast, examples such as Prieto et al. (2021) accept that marginalization is an ill-defined and potentially wicked problem. Studies that adopt f- this view argue that programs can be used to advance self-determination to redress inclusion barriers such as structural racism. No Even when a theory was discussed, few studies sought to understand the underlying tF mechanisms that would contribute to either intended or actual change, and even fewer lV ina sought to build theory related to the domain of scholarly impact. This omission is noteworthy because the authors that did engage in reflective practice pointed to the need for further work to better understand the needs of marginalized individuals. Most er mentioned the need to unpack the implicit assumptions underlying the relationship between n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education training and change. In terms of pedagogical design, Littenberg-Tobias and Reich (2020) also suggest that marginalized individuals may lack the self-regulated study patterns required to succeed in MOOCs. Alaref et al. (2020, p.12) illustrate that the findings of Academy of Management Learning & Education authors such as Mishra (2014), who call for a nuanced approach to the needs of the marginalized, may be lacking. The authors examine an unsuccessful program in Tunisia, R er Pe concluding that additional research is required to examine “alternative design modalities that may enhance program e ectiveness” (Alaref et al., 2020, p.12). Implicit assumptions relating to the types of training for different marginalized groups ie ev We found that the training offered seemed to differ across forms of marginalization. For example, in papers where socioeconomic status (Andrewartha & Harvey, 2017; Mishra, 2014), unemployment (Anosike, 2018; Nafukho, Machuma, & Muyia, 2010), and w developing nation (Co & Mitchell, 2006; Hope, 2012)3 were the primary forms of Pr marginalization, there appeared to be an implicit assumption that increased employment oo and education could redress income inequities. However, these articles provided little empirical evidence to support these assumptions, as they primarily focused on capability f- outcome measures with little attention to impact. Regarding gender, programs were No predominantly designed to increase female engagement in higher education to increase economic and social contributions beyond domestic duties (Ibeh & Debrah, 2011; Wang, tF 2020). They also sought to overcome perceived barriers to increased economic lV ina engagement, such as a lack of assertiveness (Morgan & Leung, 1980; Riebe, 2012). While this may be appropriate for certain types of marginalized programs, it was unclear as to whether these were real needs supported by evidence or simply assumptions drawn from er unconscious bias and neoliberal ideals. By contrast, where persons with disabilities were 3 n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 18 of 42 This includes three developing countries or areas: Kenya (Hope, 2012), Tunisia (Alaref et al., 2020), and Sub-Saharan Africa (Kabongo & Okpara, 2010). It also included Iran (Karimi et al., 2016) and South Africa (Co & Mitchell, 2006), who are transitioning from "developing" to "developed" nations, as well as Mexico (Calderon, Cunha, & De Giorgi, 2020). Page 19 of 42 the primary form of marginalization, the papers reported empirical support focused on building confidence and social capital as well as improving community resources (Morgan R er Pe & Leung, 1980). Importantly, this includes qualitative studies that include the voice of persons with disabilities in the results (Rodríguez, Izuzquiza, & Cabrera, 2021; Shaheen, 2016). ie ev It is also worthwhile noting that 79% of the articles included an author who shared a geographic link with the focal country,4 which may indicate bias in what contexts training programs for marginalized groups are studied. w Pr Pedagogy Design, Outcomes, and Impact oo Across the empirical articles, 28 provided sufficient detail to determine the pedagogy underpinning the training program. Of these, 20 used one dominant form of pedagogy, with f- the most common being supply (13), followed by competency-based (4), and then demand- No based (3). The other 8 articles providing detail on pedagogy employed a hybrid approach, combining either supply and demand (4), supply and competency (2), demand and competency (1), or all three (1). lV ina tF Programs that failed to achieve their intended objectives were more likely to exclusively use a supply-based pedagogy. Almost three-quarters of the studies that specified pedagogy (71%) examined a supply-based approach either exclusively or in combination with er demand-based and/or a competency model. Supply-based approaches were typically used n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education by MOOCs (e.g., Bulger et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018) of less than one year in duration 4 65% of the articles, the geographical location of the first author's university matched that of the country of analysis. The remaining papers included another co-author with a geographic link. Academy of Management Learning & Education and the instructors were not trained to cater to the specific needs of marginalized groups. In fact, the articles in our corpus suggest that supply-based programs may exacerbate R er Pe marginalization (see Dillahunt et al., 2014; Halkic & Arnold, 2019; Littenberg-Tobias & Reich, 2020). This is because of implicit assumptions in the program’s design, like the assumption that participants have access to the resources required to complete the program, ie ev internet access, time, financial capacity, etc. (Dillahunt et al., 2014), or that the needs of the marginalized are homogeneous (Halkic & Arnold, 2019) or that those needs are the same as non-marginalized students (Littenberg-Tobias & Reich 2020). w By contrast, programs using a hybrid approach achieved better results. These programs Pr were more likely to achieve their outcomes and impacts than supply-based approaches, oo particularly in terms of well-being. They also used delivery partners to tailor the program to address specific learning needs or target barriers marginalized groups experience f- (Shaheen, 2016). These programs included internships and worksite visits (Co & Mitchell, No 2006; Shaheen, 2016) and involved educators who had experience or specific training pertinent to the needs of the targeted marginalized group (Anosike, 2019; Jackson et al., tF 2020). As an interesting example, Kizilcec and Kambhampaty (2020) found that increasing lV ina gender diversity in training instructors (i.e., increasing the number of female instructors), also increased the enrolment of women and was a stronger predictor than other diversity cues, such as the instructor’s skin color. Other common elements of good practice included er financial support for people to participate (Chen et al., 2018), “action learning” methods n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 20 of 42 (Taylor et al., 2004) including “community engagement-based learning methods” (Jackson et al., 2020; Prieto et al., 2021), goal alignment between the program and social mission of the university (Archibald et al., 2016; O’Brien et al., 2019; Subotzky 1999), as well as Page 21 of 42 mentoring and other social networks (Bjorvatn & Tungodden, 2010; Payton, Suarez Brown, & Smith Lamar, 2012). R er Pe DISCUSSION Our analysis of the peer-reviewed research yields new insight for designing and delivering courses to the marginalized relevant for academics, business schools, educators, ie ev accreditors, and funders. These insights can be packaged into three opportunities relating to the overall grand challenge of reframing how the outcomes and impacts of such w programs are measured. They involve conceptualizing impact, designing for impact, and sharing knowledge regarding impact. Each of these opportunities is discussed in turn along Pr with their central contribution to the field of scholarly impact and theory, followed by oo recommendations for practice. f- Opportunity 1: Conceptualizing Impact Related to Programs No As a pertinent contribution to the field of scholarly impact, we show evidence that, if programs are appropriately designed, business schools can contribute to positive outcomes tF and impacts to reduce social exclusion (Taylor et al., 2004). Despite criticism that business lV ina schools reinforce rather than redress social exclusion (Özbilgin, 2009; Vijay & Nair, 2021), we provide a new perspective illustrating that programs can provide a positive impact. However, we only provide a starting point and further work is required. er Specifically, to achieve a positive impact that can be sustained, we show the need to address n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education paradoxical tensions that may emerge regarding the programs themselves. For instance, outside our review, scholars such as Easterlin (1974) show that levels of happiness and well-being do not significantly correlate with increased income and GDP. Further, while Academy of Management Learning & Education training can be instrumental in overcoming some social barriers, it cannot address all the structural issues that cause marginalization, such as systemic racism (Prieto et al., 2021; R er Pe Vijay & Nair, 2021). Thus, business schools need to ensure that training for marginalized individuals not only results in new capabilities and expanded social networks but also ensures that marginalized individuals are not segregated to, and entrenched in, low-grade ie ev employment. Program should also seek to advance overall social well-being. To inform future conceptualization of how further information on tensions regarding w individual and social well-being can be uncovered, we draw on and extend the IPW framework. The ‘analysis grid’ provided in Figure 1 shows the different types of individual Pr outcomes and impacts mentioned in existing work, as well as temporal considerations and oo different levels of impact (e.g., interpersonal, societal) that should be considered in future f- work. This is consistent with our abductive approach, where the conceptual model is refined and further developed by analyzing the findings. Notably, by abductively adapting No the IPW framework, we show that scholars should consider how education influences tF individual empowerment and a sense of choice, which in turn may build social capital within marginalized communities. Ultimately, and as shown in some of the studies in our lV ina corpus (e.g., Prieto et al., 2021; Shaheen, 2016), this can lead to greater social cohesion and improved governance toward that goal. Through our thematic analysis, we offer a theoretical contribution to the field of scholarly er impact by developing a new coherent model and by using and extending the IPW n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 22 of 42 framework to show the range of outcomes and impacts that future programs (and the evaluations of those programs) might consider. This expansive framework highlights how scholars can show evidence and the promise of impact beyond the short-term Page 23 of 42 individualistic measures used in other evaluation frameworks. The codebook provided in Appendix 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the types of outcomes and impacts that R er Pe scholars may wish to consider when conceptualizing impact in relation to such programs. While training evaluation frameworks (e.g., Ford, 2021) discuss subjective considerations, such as satisfaction with training, learning, transfer of training to the workplace, improved ie ev job performance, and return on investment, there is little work that examines collective and system-level change. Our work thus provides a novel conceptual contribution. w Our contribution is salient as the training literature largely focuses on short-term individual learner considerations, such as verbal knowledge measured through recall and motivation Pr or self-evaluation (Kraiger, Ford, & Salas, 1993; Krathwohl, 2002). Broader well-being oo outcomes are ignored, except perhaps tangentially in the more recent work on informal f- learning (e.g., Cerasoli, Alliger, Donsbach, Mathieu, Tannenbaum, & Orvis, 2018; Tews, Noe, Scheurer, & Michel, 2016). Indeed, while education frameworks, such as that offered No by Nabi et al. (2017, p. 278) include some longer-term measures such as “venture creation” tF and “business performance,” the authors acknowledge the limitations of their categorization system and call for “increased research on higher-level impact indicators” lV ina (Nabi et al., 2017, p. 289). Our expanded IPW framework responds and illuminates how traditional and salient measures such as employment, training, and income can be integrated with longitudinal measures that show impact. In short, we highlight how society er and scholars can move beyond the economic and rational measures of impact typically n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education associated with training for the marginalized to show meaningful impact across a broad range of well-being indicators. Opportunity 2: Program Design Academy of Management Learning & Education We also find evidence that further work is required to design programs for impact. Our review indicates that some supply-based programs, such as the MOOC models examined, R er Pe increase rather than decrease disparity. By contrast, hybrid models show greater evidence of impact. Thus, when designing for impact, scholars should be cognizant that when used exclusively supply-based models appear to fall short in terms of what is required to redress ie ev social exclusion. This is concerning as despite calls two decades ago to adopt pedagogies that center on shared meaning and collaborative learning (Kraiger, 2008), our study shows that supply-based pedagogies continue to dominate instruction to marginalized groups. w Consistent with Kraiger and Ford (2021), we also find the need for more theory-driven Pr approaches to pedagogy. We highlight the need for further work to examine the underlying oo relationships between programs and what is achieved through training, noting that this must f- be done through a better understanding of the needs of the marginalized and by using theory. For example, we uncover trends that may point to bias within business schools, No such as the business content offered not being directed toward objective community needs. tF In essence, theory regarding these assumptions, which may be informed by neoliberal ideals (such as well-being equals wealth), is lacking across the field. Further development lV ina of pedagogy is needed to ensure that implicit assumptions related to the characteristics and needs of marginalized individuals and communities are clearly articulated and tested. Future work should examine the influence adopting such ideas has on their institution. The er results of our analysis thus offer room to advance the literature, contributing to future n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 24 of 42 understanding of the theory of change that sits behind program design. The literature may also broaden in terms of the implicit assumptions that underpin the programs. Studies that Page 25 of 42 adopted this reflective approach show that it was these implicit assumptions that influenced program outcomes and impact. R er Pe In addition, we show that program success requires the voice of the marginalized to be integrated into programs (Rodríguez-Hernández, Cascallar, & Knydt, 2020). Programs need to be undertaken “with the community, not to the community” (O’Brien et al., 2019, ie ev p. 399). Indeed, community-based participatory models offer great promise (see Wang, 2020; Prieto et al., 2021). For many business schools, that represents a shift toward "joint w ownership" models that meet the needs and interests of the community and collaborating partners (Subotzky, 1999, p. 427). Our review shows that business schools may be well Pr placed to do this; however, the research-practice lag must be addressed to integrate lessons oo learned more broadly across the field. f- Opportunity 3: Sharing Knowledge Regarding Impact No Our findings also show the need for more research as results in the field currently lack cohesion. As argued earlier, researchers must acknowledge the complex nature of the tF environment in which these programs operate. They must allow for a feedback loop lV ina between the results that scholars perceive as possible at the outset of the program versus what was achieved, and that includes both positive and unintended negative consequences. However, we find that the field is currently dominated by incoherent interpretations and an er over-emphasis on short-term outcomes at the individual level. Scant literature relates to n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education individual and system-level impacts, such as respect for nature and sustainable development (apart from the study by Hope, 2012). We also find a lack of attention to broader social implications, which raises the need for an expansive and coherent view of Academy of Management Learning & Education impacts that considers the full range of stakeholders involved, not to mention the tensions that might arise. R er Pe We also find shortcomings in studies published to date. While we do not seek to engage in the debate regarding the merits of the academic publication process, we do highlight that peer-reviewed journals provide a sample source to understand tensions and trade-offs that ie ev emerge when conceptualizing impact. It is disappointing that more studies have not yet been published in this field. It is also concerning that a quarter of the empirical studies w (24%) did not identify the data collection methods used given that all articles included in our sample feature in peer-reviewed outlets and should be subject to scholarly standards Pr that command transparency and replicability. We hope that our review inspires scholars to oo engage in high-quality research that can be reviewed and ultimately shared through the peer-review process. f- In addressing this gap, our analysis specifically reveals the need for more studies related to No consciousness outcome measures. While all articles analyzed refer to the achievement of tF individual behavioral and cognitive outcomes, other studies suggest that these changes can result in (and are supported by) positive consciousness outcomes. However, the latter is lV ina less studied than the former. We also highlight the need for further longitudinal studies in peer-reviewed research. Such studies should consider the range of stakeholders involved, including the marginalized, the community, and the scholars delivering the programs. The er expanded conceptual framework that we develop in this review, as summarized in Figure n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 26 of 42 1, shows the range of outcome and impact measures that such studies could examine. Institutional influences also warrant further attention. Most studies examine US data, and no studies pertain to China or Indonesia, which is concerning given these nations are among Academy of Management Learning & Education Page 27 of 42 the most populated in the world. We also find limited research across classifications of marginalization, such as people who identify as LGBT, military veterans, and Indigenous R er Pe people. Gaps also remain in relation to other salient settings, such as economic shocks or natural disasters. Future research could be well-suited to large-scale statistical analysis. We highlight that research, while not perfect, does provide a powerful means of uncovering ie ev new knowledge—knowledge that is rooted in theoretical advancement. Research also helps us understand how the life circumstances of marginalized people across the world can be w advanced according to the principles of sustainable development (Painter-Morland et al., 2017). Our review and critical analysis thus provide a platform for future program design Pr that allows for the integration of these areas and further ongoing evaluation to assess the oo appropriateness of teaching goals, the knowledge emphasized, the impact on the educators f- and business schools involved, and the pedagogy design. Our examination shows that some management scholars indeed seek to use knowledge from our discipline to advance and No achieve social good and to publish and disseminate this information. However, as argued above, further studies are needed. lV ina Implications for Practice tF Beyond the field of scholarly impact, our results offer insight for practitioners. Our review highlights the need for future attention assessing the seriousness of training provider efforts er in delivering positive outcomes and impacts at the individual, collective, and societal levels n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 for marginalized people across the world and over time. It is possible that such initiatives are simply forms of marketing spin—lip-service paid to the espoused social sustainability/justice purposes of the institution (Subotzky, 1999; Wang, 2020). Our results Academy of Management Learning & Education highlight that it is important to engage in further work to identify elements that demonstrate a substantive attempt at achieving tangible improvements in social outcomes (e.g., R er Pe resourcing). Notably, the objectives discussed in the papers that we examined were broader than existing educational evaluation frameworks, such as those offered by Kraiger et al. (1993) and in Bloom’s taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002). ie ev For education accreditation agencies such as the AACSB, our research provides new insight into strategies that may nudge higher education institutions toward greater social w inclusion. Specifically, we find that goal alignment is important (Subotzky, 1999). Namely, scholars within the field argue that successful programs require reciprocity, meaning that Pr the program needs to deliver benefits to both the community and the higher education oo provider, or even the system itself. As an illustration, in considering how a university’s f- entrepreneurial ecosystem could be expanded to include underrepresented communities, O’Brien et al. (2019, p. 399), find that a university’s involvement in such programs No typically rests on the “core values, mission, attributes, objectives and culture of a tF university.” Accreditation agencies, such as the AACSB (2022, para. 1), provide platforms to create conditions under which this may occur by encouraging “a shared sense of lV ina responsibility to have a positive impact on society.” The opportunity exists to strengthen the evidence as to whether this goal is being achieved, as offering programs alone is not sufficient to have an impact. Greater attention needs to be paid to associated consciousness er outcomes and collective social and system impacts to improve current practice. n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 28 of 42 For policymakers and other entities like NGOs and philanthropists who wish to fund training programs for the marginalized, we offer two important insights. First, we find that supply-based models achieve limited outcomes and rarely consider or achieve Page 29 of 42 consciousness outcomes and collective social and system impacts. To address inequality, funding agencies may wish to consider hybrid models that include action or community- R er Pe based learning (Jackson et al., 2020; Prieto et al., 2021). Further, funders may wish to include a requirement of community involvement in the design and delivery of programs (O'Brien et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2020). Second, funders can heed our call ie ev for further research when allocating their resources. Further knowledge is required, given several of the programs examined either over or underachieved in their initial goals. Thus, it is prudent for funders to invest in generating further knowledge to establish programs w that are both realistic and transparent in relation to the associated outcomes and impact. Pr We also show that an opportunity exists for these evaluations to be undertaken in a oo systematic and peer-reviewed fashion in collaboration with academics to advance both practice and theory. Toward this goal, one avenue may include creating a special issue f- group (e.g., within the Academy of Management or Principles for Responsible No Management Education (2022) networks) through which program results are exchanged. Authors should also submit data files within journal submissions to allow scholars to tF analyze and compare results across programs and contexts. Such action may support further lV ina understanding of the global dimensions of business school training programs delivered to marginalized individuals and their impacts. Like all studies, our findings are subject to limitations that point to areas for further er investigation. The most significant is the scope of our review, which was confined to peer- n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education reviewed research that examined business training programs delivered to marginalized individuals. The benefit of this approach is that it provides the first complete map of the literature on which scholars can build. Specifically, we show what has been studied, by Page 30 of 42 Academy of Management Learning & Education who, how, and over what time. However, we acknowledge that peer-reviewed research is subject to limitations, including potential “selection biases,” in those journals might seek R er Pe to publish positive results (Kunisch et al., 2018, p. 521). While we did not find this (e.g., as shown in Table 1 and noted above, studies report negative results), we nevertheless accept this limitation and suggest that future studies could expand our work to include ie ev unpublished work (i.e., grey material) in the fashion of a meta-analysis. While it is beyond the scope of our review to conclude that the limitations that we observed in the sample would extend to grey material, we provide a fruitful analysis of the tensions and trade-offs w that future examinations of such work could consider. Scholars could also conduct new Pr empirical work to examine if business schools across the world have access to in-house oo program evaluations that could be empirically examined. However, authors pursuing this avenue should take care to ensure that the view of the marginalized is appropriately f- captured in their voice (see Bhatt et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2020). No Another limitation pertains to the IPW framework itself. The framework put forward by tF Painter-Morland et al. (2017) and expanded here requires further consideration. More information needs to be collected to assess how efforts to harmonize tensions and trade- lV ina offs unfold over time. Future studies could therefore undertake a cross-comparison analysis to consider the outcomes and impacts achieved across different cohorts and different methods of delivery options, such as business schools versus community-based training er providers. Another option to extend our work is to examine complementary activities, such n sio 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 as pre-entry university programs that provide social support to assist students to adapt to university life. While Thomas (2011) provides a review of the literature in this domain, the authors find limited research regarding scholarly impact, including evaluations on the Page 31 of 42 effect of pre-entry interventions on students’ retention and success in higher education. More recent work by scholars such as Rodríguez, Tinajero and Páramo (2017) supports R er Pe that this remains a knowledge gap. ie ev CONCLUSION It is our aim with this paper to map the literature to show how scholars conceptualize impact w in the context of university business training delivered to marginalized individuals as well as the ends achieved. We find incoherence in the field that requires synthesis. We also Pr reveal the need for a broader view of evaluations that extends beyond traditional education oo frameworks to consider individual, collective, and system-level subjective outcomes and f- impacts. Using this framework, we highlight that future training requires new knowledge contextualized to the person as well as the environment in which they live. We also find No teaching methods that engage the marginalized in the design and delivery of programs and tF tailor the forms of communication, as well as use of education technologies, are more likely to achieve their intended impacts than traditional supply-based modes of learning. lV ina Scholars, educators, accreditor agencies, funding agencies, and policymakers can draw on our findings to advance future research and practice that seeks to use business education to redress social inequality. n sio er 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education Academy of Management Learning & Education 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 Pe FIGURE 1: er Re First-order codes* Capabilities Education Employment Financial security Health vie Choice Perceived freedom Identity Life satisfaction Level 1: Measures during the program Level 2: Pre- and post-program measures Level 3: Measures between 0 and 3 years Level 4: Measures between 3 to 10 years Explicit theory Implicit assumptions about marginalized individuals Disadvantage Underrepresented Developing nation Unemployed ** Page 32 of 42 Emerging data structure w Third-order Core concepts Second-order themes Pr Individual behavioral and cognitive (Individual objective) Individual consciousness (Intra-subjective) Evaluation Individual Outcomes Collective Impact (short-term measures) (longitudinal measures) Behavioral and cognitive outcomes (Individual objective) Collective social (Inter-subjective) Consciousness (Intra-subjective) System (Inter-objective) oo f- No Research Design Theory of change Program Design Forms of marginalization First-order codes* Second-order themes Analysis grid examining the relationship between individuallevel outcomes and collective impact Overcoming or avoiding loneliness Social capital Social cohesion Social relationships Collective social (Inter-subjective) Community benefits Good governance Community resources Respect for nature tF System (Inter-objective) ina lV Pedagogy/ Teaching model ers Supply Demand Competency Hybrid *Illustrative text provided in Appendix 2 ion Page 33 of 42 References Aguinis, H., Shapiro, D., Antonacopoulou, E., & Cummings, T. 2014. Scholarly impact: A pluralist conceptualization. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 13(4): 623–639. Alaref, J., Brodmann, S., & Premand, P. 2020. The medium-term impact of entrepreneurship education on labor market outcomes: Experimental evidence from university graduates in Tunisia. Labour Economics, 62(C): 1–18. Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. 2020. The problematizing review: A counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s argument for integrative reviews. Journal of Management Studies, 57(6): 1290–1304. Andrewartha, L., & Harvey, A. 2017. Employability and student equity in higher education: The role of university careers services. Australian Journal of Career Development, 26(2), 71–80. Anosike, P. 2018. Entrepreneurship education knowledge transfer in a conflict Sub-Saharan African context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(4): 591–608. Anosike, P. 2019. Entrepreneurship education as human capital: Implications for youth self-employment and conflict mitigation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Industry and Higher Education, 33(1): 42–54. Archibald, P., Muhammad, O., & Estreet, A. 2016. Business in social work education: A historically black university’s social work entrepreneurship project. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(1): 79– 94. Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). 2022. AACSB Accreditation Overview. https://www.aacsb.edu/educators/accreditation/business-accreditation. Bacq, S., Drover, W., & Kim, P. 2021. Writing bold, broad, and rigorous review articles in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(6): 1–8. Bhatt, B., Qureshi, I., & Sutter, C. (2022). How do intermediaries build inclusive markets? The role of the social context. Journal of Management Studies, 59(4), 925–957. Bjorvatn, K., & Tungodden, B. 2010. Teaching business in Tanzania: Evaluating participation and performance. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(2-3): 561–570. Bulger, M., Bright, J., & Cobo, C. 2015. The real component of virtual learning: Motivations for faceto-face MOOC meetings in developing and industrialised countries. Information, Communication & Society, 18(10): 1200–1216. Calderon, G., Cunha, J. M., & De Giorgi, G. 2020. Business literacy and development: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in rural Mexico. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 68(2): 507– 540. Cerasoli, C. P., Alliger, G. M., Donsbach, J. S., Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Orvis, K. A. 2018. Antecedents and outcomes of informal learning behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(2), 203–230. Chakravarty, S., Lundberg, M., Nikolov, P., & Zenker, J. 2019. Vocational training programs and youth labor market outcomes: Evidence from Nepal. Journal of Development Economics, 136(C): 71–110. Chen, G., Davis, D., Krause, M., Aivaloglou, E., Hauff, C., & Houben, G. 2018. From learners to earners: Enabling MOOC learners to apply their skills and earn money in an online market place. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 11(2): 264–274. Co, M. J., & Mitchell, B. 2006. Entrepreneurship education in South Africa: A nationwide survey. Education + Training, 48(5): 348–359. Dillahunt, T., Wang, B., & Teasley, S. 2014. Democratizing higher education: Exploring MOOC use among those who cannot afford a formal education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(5): 177–196. Doucette, M., Gladstone, J., & Carter, T. 2021. Indigenous conversational approach to history and business education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(3): 473–484. Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz. New York: Academic Press. Fairlie, R., & Krashinsky, A. 2012. Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship revisited. The Review of Income and Wealth, 58(2): 279–306. Fayolle, A. 2013. Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(7-8): 692–701. Ford, J. K. (2021). Learning in organizations: An evidence-based approach. New York: Routledge. Gainsford, A., & Evans, M. 2021. Integrating andragogical philosophy with Indigenous teaching and learning. Management Learning, 52(5): 559–580. Girei, E. 2017. Decolonising management knowledge: A reflexive journey as practitioner and researcher in Uganda. Management Learning, 48(4): 453–470. Habel, C., & Whitman, K. 2016. Opening spaces of academic culture: Doors of perception; heaven and hell. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(1): 71–83. w ie ev R er Pe f- oo Pr n sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education Academy of Management Learning & Education Haley, U., Cooper, C., Hoffman, A., Pitsis, T., & Greenberg, D. 2020. Learning and education strategies for scholarly impact: Influencing regulation, policy and society through research. Academy of Management Learning & Education Special Issue Call. https://aom.org/docs/defaultsource/publishing-withaom/amle_special_issue_call_strategies_for_scholarly_impact.pdf?sfvrsn=713ff196_2. Accessed 21 May 2021. Haley, U., Page, M., Pitsis, T., Rivas, J., & Yu, K. 2017. Measuring and achieving scholarly impact: A report from the Academy of Management’s practice theme committee. Academy of Management, Briar Cliff, New York. http://aom.org/About-AOM/StrategicPlan/Scholarly-ImpactReport.aspx?terms=measuring%20and%20achieving%20scholarly%20impact. Accessed 21 May 2021. Halkic, B., & Arnold, P. 2019. Refugees and online education: Student perspectives on need and support in the context of (online) higher education. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(3): 345–364. Hickel, J. (2021). What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations, 18(7): 1105– 1111. Hinson, R., & Amidu, M. 2006. Internet adoption amongst final year students in Ghana’s oldest business school. Library Review, 55(5): 314–323. Hope, K. 2012. Engaging the youth in Kenya: Empowerment, education, and employment. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 17(4): 221–236. Ibeh, K., & Debrah, Y. A. 2011. Female talent development and African business schools. Journal of World Business, 46(1), 42–49. Jackson, M., Colvin, A., & Bullock, A. 2020. Development of a pre-college program for foster youth: Opportunities and challenges of program implementation. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(3): 411–423. Kabongo, J., & Okpara, J. 2010. Entrepreneurship education in Sub Saharan African universities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(4): 296–308. Karimi, S., Biemans, H., Lans, T., Chizari, M., & Mulder, M. 2016. The impact of entrepreneurship education: A study of Iranian students’ entrepreneurial intentions and opportunity identification. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1): 187–209. Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1976. Evaluation of training. In R L. Craig (Ed.), Training and Development Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill. Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1994. Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler. Kitchener, M., & Delbridge, R. (2020). Lessons from creating a business school for public good: Obliquity, waysetting, and wayfinding in substantively rational change. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 19(3), 307–322. Kizilcec, R., & Kambhampaty, A. 2020. Identifying course characteristics associated with sociodemographic variation in enrolments across 159 online courses from 20 institutions. PLoS ONE, 15(10): 1–19. Kraiger, K. 2008. Transforming our models of learning and development: Web-based instruction as enabler of third-generation instruction. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(4): 454-467. Kraiger, K., Ford, J., & Salas, E. 1993. Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2): 311– 328. Kraiger, K., & Ford, J. K. 2021. The science of workplace instruction: Learning and development applied to work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1): 45–72. Krathwohl, D. 2002. A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4): 212– 218. Kunisch, S., Menz, M., Bartunek, J. M., Cardinal, L. B., & Denyer, D. (2018). Feature topic at organizational research methods: How to conduct rigorous and impactful literature reviews?. Organizational Research Methods, 21(3), 519–523. Littenberg-Tobias, J., & Reich, J. 2020. Evaluating access, quality, and equity in online learning: A case study of a MOOC-based blended professional degree program. The Internet and Higher Education, 47: 1–11. Loviscek, A., & Cloutier, N. 1997. Supplemental instruction and the enhancement of student performance in economics principles. The American Economist, 41(2): 70–76. MacIntosh, R., Beech, N., Bartunek, J., Mason, K., Cooke, B., & Denyer, D. 2017. Impact and management research: Exploring relationships between temporality, dialogue, reflexivity and praxis. British Journal of Management, 28(1): 3–13. Majee, W., Long, S., & Smith, D. 2012. Engaging the underserved in community leadership development: Step up to leadership graduates in northwest Missouri tell their stories. Community Development, 43(1), 80–94. w ie ev R er Pe f- oo Pr n sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 34 of 42 Page 35 of 42 Macleod, H., Haywood, J., Woodgate, A., & Alkhatnai, M. 2015. Emerging patterns in MOOCs: Learners, course designs and directions. TechTrends, 59(1): 56–63. Mishra, M. 2014. Vertically integrated skill development and vocational training for socioeconomically marginalized youth: The experience at Gram Tarang and Centurion University, India. Prospects, 44(2): 297–316. Morgan, B., & Leung, P. 1980. Effects of assertion training on acceptance of disability by physically disabled university students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27(2): 209. Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. 2017. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2): 277–299. Nafukho, F., Machuma, A., & Muyia, M. 2010. Entrepreneurship and socio-economic development in Africa: A reality or myth? Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(2): 96–109. Newcomer, K., Hatry, H., & Wholey, J. 2015. Handbook of practical program evaluation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. O’Brien, E., Cooney, T., & Blenker, P. 2019. Expanding university entrepreneurial ecosystems to underrepresented communities. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 8(3): 384–407. OECD. 2020. Tackling coronavirus (COVID-19): Focus on social challenges. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/themes/social-challenges. Accessed 19 May 2021. OECD. 2021. Social impact measurement for the social and solidarity economy. https://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/d20a57acen.pdf?expires=1635725289&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=1CED329D2355CC7D36BE8FB166 3CA2B4. Accessed 1 November 2021. Özbilgin, M. 2009. From journal rankings to making sense of the world. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(1): 113–121. Painter-Morland, M., Demuijnck, G., & Ornati, S. 2017. Sustainable development and well-being: A philosophical challenge. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(2): 295–311. Paul, J., & Criado, A. R. 2020. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know?. International Business Review, 29(4), 1–7. Payton, F., Suarez-Brown, T., & Smith Lamar, C. 2012. Applying IRSS theory: The Clark Atlanta University exemplar. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 10(4): 495–513. Piketty, T. 2020. Capital and ideology. Cambridge, MS: Harvard University Press. Prieto, L., Phipps, S., Stott, N., & Giugni, L. 2021. Teaching (cooperative) business: The ‘Bluefield Experiment’ and the future of black business schools. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(3): 320–341. Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME). 2022. What is PRME. https://www.unprme.org/about. Accessed 18 June 2022. Productivity Commission. 2019. The demand driven university system: A mixed report card. Commission Research Paper, Canberra. Riebe, M. 2012. A place of her own: The case for university-based centers for women entrepreneurs. Journal of Education for Business, 87(4): 241–246. Rittel, H., & Webber, M. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4: 155–169. Rodríguez, P., Izuzquiza, D., & Cabrera, A. 2021. Inclusive education at a Spanish university: The voice of students with intellectual disability. Disability & Society, 36(3), 376–398. Rodríguez, M., Tinajero, C., & Páramo, M. 2017. Pre-entry characteristics, perceived social support, adjustment and academic achievement in first-year Spanish university students: A path model. The Journal of Psychology, 151(8): 722–738. Rodríguez-Hernández, C., Cascallar, E., & Knydt, E. 2020. Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 29(100305): 2– 24. Salmi, J. 2020. COVID’s lessons for global higher education. Lumina Foundation, https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/covids-lessons-for-global-highereducation.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2021. Scott, L., Dolan, C., Johnstone-Lois, M., Sugden, K., Wu, M. 2012. Enterprise and inequality: A study of Avon in South Africa. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3): 544–568. Shaheen, G. 2016. Inclusive entrepreneurship: A process for improving self-employment for people with disabilities. Journal of Policy Practice, 15(1-2): 58–81. Simpson, R. 2006. Masculinity and management education: Feminizing the MBA. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(2): 182–193. Sitzmann, T., & Campbell, E. 2021. The hidden cost of prayer: Religiosity and the gender wage gap. Academy of Management Journal, 64(4): 1016–1048. w ie ev R er Pe f- oo Pr n sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education Academy of Management Learning & Education Sitzmann, T., & Weinhardt, J. M. 2019. Approaching evaluation from a multilevel perspective: A comprehensive analysis of the indicators of training effectiveness. Human Resource Management Review, 29(2): 253-269. Spicer, A., Jaser, Z., & Wiertz, C. 2021. The future of the business school: Finding hope in alternative pasts. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(3): 459–466. Subotzky, G. 1999. Alternatives to the entrepreneurial university: New modes of knowledge production in community service programs, Higher Education, 38(4): 401–440. Taylor, D., Jones, O., & Boles, K. 2004. Building social capital through action learning: An insight into the entrepreneur, Education + Training, 46(5): 226–235. Tews, M. J., Noe, R. A., Scheurer, A. J., & Michel, J. W. 2016. The relationships of work–family conflict and core self-evaluations with informal learning in a managerial context. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(1), 92–110. Thomas, L. 2011. Do pre entry interventions such as ‘Aim higher’ impact on student retention and success? A review of the literature. Higher Education Quarterly, 65(3): 230–250. Vijay, D., & Nair, V. G. 2021. In the name of merit: Ethical violence and inequality at a business school. Journal of Business Ethics. Ahead of print: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-02104824-1 Vitartas, P., Ambrose, K., Millar, H., & Dang, T. 2015. Fostering Indigenous students’ participation in business education. International Journal of Learning in Social Contexts, 17: 84–94. Wang, Q. 2020. Higher education institutions and entrepreneurship in underserved communities. Higher Education, 2(9): 1–19. Wilson, B., & Rossig, S. 2014. Does supplemental instruction for principles of economics improve outcomes for traditionally underrepresented minorities? International Review of Economics Education, 17(C): 98–108. w ie ev R er Pe f- oo Pr n sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 36 of 42 Page 37 of 42 Cons. Beh. Cul. Sys. L4 X A=I X X Andrewartha & Harvey 2017 PD Australia No theory NA NA A=I X NA Anosike 2019 ENT Nigeria Entrepreneurship Education L1 X A=I A X Anosike 2018 ENT Nigeria Entrepreneurship Education L1 X I<A A NA 2016 ENT USA Self-directed theory L2 X A=I A A 2010 ENT Tanzania No theory L1 NA A=I NA NA Bulger et al. 2015 MD Global Learning theory L2 NA I<A A=I X Calderon et al. 2020 ENT Mexico No theory L3 NA A=I X A=I Chen et al. 2018 DA Global Self-Regulated Learning L2 X A=I NA NA 2006 ENT South Africa No theory NA NA I>A A A 2014 MD USA MOOC model L1 NA I>A NA NA Doyle 2011 PD Australia NA X X X X Gainsford & Evans 2021 MD Australia L3 X A=I A=I A=I Garcia 2021 LD USA NS L2 X A=I A=I A=I Habel & Whitman 2016 MD Australia NS L1 X I I>A A=I Halkic & Arnold 2019 MD Germany L2 X A=I A=I I Hinson & Amidu 2006 IT Ghana Internet Benefit Model NS L1 NA A=I A=I A=I Hope 2012 ENT Kenya No theory NA Ibeh et al. 2008 MGT Global No theory NS Ibeh & Debrah 2011 BUS SubSaharan Africa No theory NS Jackson et al. 2020 LD USA Social Capital Theory No theory w Pedagogy (iii) Pr Iran Kizilcec & Kambhampat y 2020 MD Global Kolb 1981 PD USA LittenbergTobias & Reich 2020 SCM USA Theory of Planned Behavior Psychologically inclusive design cues X X NA NA NA NA A=I A=I A=I L1 X A=I A=I A=I NA X A=I X A=I NA NA L2 A=I L1 X No theory L1 A=I Grounded theory L1 X A=I NA NA n sio ENT NA er 2016 lV ina Karimi et al. NS tF ENT NA No 2010 Systems theory & Personcentered theory Indigenous Standpoint Theory Participation Action Research Bourdieuian framework Innovative Academic Model f- Kabongo & Okpara SubSaharan Africa NS oo Co & Mitchell Dillahunt et al. ie ev Archibald et al. Bjorvatn & Tungodden Sys. Theory of Change Cul. Tunisia Beh. ENT Cons. 2020 Data Coll. Method Country of Analysis Alaref et al. Theoretical Perspective Discipline (i) Outcome/Impact Achieved (v) Publication Year Research Method (iv) Conceptualized Outcome/ Impact Authors Marginalized Group (ii) TABLE 1: Details of articles included in study R er Pe 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education A=I A NA A=I A=I NA A=I X NA A=I X X Academy of Management Learning & Education w ie ev R er Pe f- oo Pr n sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 38 of 42 Page 39 of 42 APPENDIX 1: Corpus selection* Journal search using Web of Science and Scopus databases Search 1 Search 2 Search 3 Keywords (First Search) "Disadvantaged" OR “Marginalized” OR “At-risk” OR “Underrepresented” AND "University" AND "Training" OR "Short course" OR "Certificate" OR "Diploma" OR "Advanced Diploma" OR "Micro-credentials" OR "Pre-entry" OR "MOOCs" OR "SPOCs" Keywords (Second Search) "Disadvantaged" OR “Marginalized” OR “At-risk” OR “Underrepresented” AND "University" AND "Pre-college program" OR "Supplemental Instruction course" OR "School Outreach Program" OR "Information skills" OR "Foundation studies" Keywords (Third Search) "University" OR "Business School" AND "Training" OR "Program" AND "Indigenous" OR "Disabled" OR "Low socio*economic status" OR "Military veteran" OR "lesbian" OR "gay" OR "homosexual" OR "bisexual" OR "intersex" Step 1. Database search results (Excluding book chapters, non-English articles and conference proceedings) ie ev R er Pe Step 1. Database search results (Excluding non-English articles and conference proceedings) n = 1806 n = 577 Exclude Step 3. Exclusion based on subject area n = 124 Pr Step 4. Title & Abstract Review n = 398 Step 3. Exclusion based on subject area n = 759 Exclude Step 4. Title & Abstract Review n = 336 oo Exclude Step 2. Duplicates n= 85 Exclude Step 3. Exclusion based on subject area n = 875 Exclude n = 1143 Step 2. Duplicates n = 36 Step 2. Duplicates n = 514 w Step 4. Title & Abstract Review n = 384 Exclude Articles approved for coding n = 100 19 articles selected Articles approved for coding n=8 81 articles selected f- Step 5. Comprehensive review, exclusion of = 84 Articles included n = 16 Step 6. Additional reference search n = 15 included Step 5. Comprehensive review, exclusion of n = 3 Articles included n = 5 Step 6. Additional reference search n = 7 included Total articles included n =12 tF Total articles included n = 31 (1st & 2nd search) n No Total articles included in Review n = 43 lV ina * Subject areas such as business, management, accounting, economics, econometrics and finance were included, but areas such as medicine and science were not. n sio er 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education Academy of Management Learning & Education APPENDIX 2: Coding scheme First-order codes 1.1 Capabilities Illustrative text and statements from articles coded New skills and knowledge, including: Ability to control emotions; ability to excel; avoiding risky behaviors; business literacy; cognitive skills; college readiness; communication; competencies/performance; completing a business plan or ability to navigate services; creativity; critical thinking; employment skill development; entrepreneurial intention; healthy relationship skill development; healthy behaviors; independence; information-seeking skills; intellectual growth; leadership skills; not being defined by a disability; note-taking skills; perseverance; problem-solving; resilience; selfmanagement; self-regulation; self-efficacy; social competence; soft skills; stress management; study skills; teamwork; test-taking skills; time management; work ethic; volunteering Participation, and completion of an education or training program, including: Completion; decreased absenteeism; educational attainment; educational outcomes; enrolment; grades; participation in training and/or education Capacity to gain and sustain employment, including: Ability to gain employment; career development; entry-level; employability; increases in employment; reduction in unemployment; self-employed; small business start-up Achievement of financial independence, financial self-interest, securing basic resources to sustain life, including: Access to capital; debt; decreased vulnerability to poverty; income; microfinance; understanding of (and agency in relation to) labor laws, including fair and minimum wages Positive physical health; positive mental health Understanding and enactment of alternative options available: Awareness about employer (or other) expectations; choice of rehabilitation plan for people with a disability; decreased vulnerability to involvement in armed conflict; discussing highlights or challenges; empowerment; increased awareness of the negative social and economic consequences of self-action; life path chosen; not forced down one path career choice; minimizing displeasure (pain avoidance); reduction in bullying behavior and mobbing; positive intentions; volition Level of autonomy; freedom to make the choice; motivation; opportunity identification and/or exploitation; options; participating in economic, social, political, cultural and religious life without fear or favor; self-efficacy Perceptions of self-worth, confidence in oneself, sense of purpose, improved understanding of self, including: Accountability; confidence; lessons learned; moral character; not being defined by a disability; participants ability to identify environments where they might do better based upon the knowledge and skills obtained during the program; self-insight through reflection, self-worth; sense of purpose Happiness; increased satisfaction; the consistent presence of positive mood; the consistent absence of negative mood; positive emotions Inclusion; no longer being alone; no longer feeling excluded; inclusion; reduction in isolation through social activities R er Pe 1.2 Education 1.3 Employment 1.4 Financial security 1.5 Health 2.1 Choice w ie ev 2.2 Perceived freedom Improvement for the larger community, including: Business creation; decreased turn-over; citizens realize their fullest potential; development of toolkits and other resources that could be used by the community; improved economy through business success and profits; increased employment; Millennium Development Goals; reduced crime; social innovation; social/national development process; social renewal; winning grants that benefit the community Individuals know how to conduct themselves and business properly, including climate of trust; compliance with the rule of law; collective respect of cultural belief systems and ethical values; control of corruption; equal opportunity; equity and accessibility of services; individuals understand written and unwritten laws; quality of institutions; rights of people with a disability upheld Improved resources and services for the marginalized, including: Attraction of investors or large employers into a region based on social and/or human capital; capacity of training staff; democratization of higher education; introduction and/or sustained services for specific groups (such as people with a disability); involvement in and/or improved functioning of business incubators; role of business schools/universities in improving social and/or human capital; supportive non-government organizations; universities becoming more relevant to the needs of society/the community; access to online services and resources n sio er 4.3 Community resources Connectedness and solidarity among groups in society, including: Belonging within an institution or social context; reduction in conflict Developing personal relationships, improved with relationships friends and family; meeting new people; making new friends Ability to gain an employee reference; meeting classmates for social gatherings; positive mentorship experiences, professional relationships and network relationships lV ina 4.2 Good governance Changed social perceptions towards marginalized individuals; shared value system; social networks, societal norms; employment references; societal connections tF 3.3 Social cohesion 3.4 Social relationships 3.5 Stable professional relationships 4.1 Community benefits No 2.4 Life satisfaction 3.1 Overcoming or avoiding loneliness 3.2 Social capital f- 2.3 Identity oo Pr 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 40 of 42 Page 41 of 42 First-order codes 4.4 Respect for nature Illustrative text and statements from articles coded Increased or improved human/environment interactions, including: Introduction of environmental stewardship programs, local community initiatives to improve natural habitats or environment; respect for nature Current and ongoing measures during the program (e.g., course grades), including: Qualitative (e.g., focus group, interviews); mixed methods (e.g., database analysis, survey data and interviews); quantitative (e.g., database & content analysis, survey); case study R er Pe 5.1 Level 1 5.2 Level 2 Pre- and post-program measures (e.g., course completion, leadership capabilities), including: Mixed methods (e.g., survey – cross-sectional & case study, interviews and focus group, database analysis); qualitative (e.g., content analysis); quantitative (e.g., experimental design, survey) 5.3 Level 3 Measures between 0 and 3 years post-program (e.g., number and type of start-ups, increase in business performance), including: Quantitative (e.g., survey longitudinal & randomized control trial); mixed methods (e.g., interviews & survey- longitudinal) Measures between 3 to 10 years post-program (e.g., survival of start-ups, ongoing self-employment), including: Quantitative (e.g., survey – longitudinal, randomized control trial) Social capital theory, entrepreneurship theory, self-regulated learning theory, theory of change, theory of planned behavior, learning theory Access to resources, e.g., the internet, required to engage in training, redress income inequities through increased employment and education, redress social exclusion based on representation through increased confidence and social capital Individuals impacted by armed conflict; people with a disability; people who are homeless or in foster care; people with low literacy &/or SES status; refugees; prisoners Ethnicity; gender; Indigenous 5.4 Level 4 6.1 Explicit theory 6.2 Implicit assumptions Individuals excluded from or outside of labor force; low labor force participation rates; high unemployment rates; youth unemployment Reproduction methods; lectures, readings, exams Active problem-solving; real-life situations; action learning Participative methods; exploration; discussion; experimentation Supply + demand, supply + competency, demand + competency, supply + demand + competency f- Supply Competency Demand Hybrid Iran; Kenya; Mexico; South Africa Sub-Saharan Africa; Tunisia oo 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Pr 7.1 Disadvantaged 7.2 Underrepresented 7.3 Developing nation 7.4 Unemployed w ie ev n sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Learning & Education Academy of Management Learning & Education Tracey Dodd ([email protected]) is a Senior Lecturer with the Adelaide R er Pe Business School, University of Adelaide and Honorary Senior Research Fellow, University of Exeter. Her research interests intersect responsible management and Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG). She earned her PhD from the University of South Australia. ie ev Chris Graves ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor with the Adelaide Business School, University of Adelaide and Director of the Family Business Education & Research Group. His research interests include entrepreneurship and family enterprise. He earned his PhD from the University of Adelaide. w Pr Janin Hentzen ([email protected]) is a Strategy Analyst with St. John oo of God Health Care. Her research spans business management, financial technology, and consumer experience. She earned her PhD from the University of Adelaide. fn sio er lV ina tF No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 42 of 42