Handout GR monday 3 - Universität Stuttgart

Anuncio

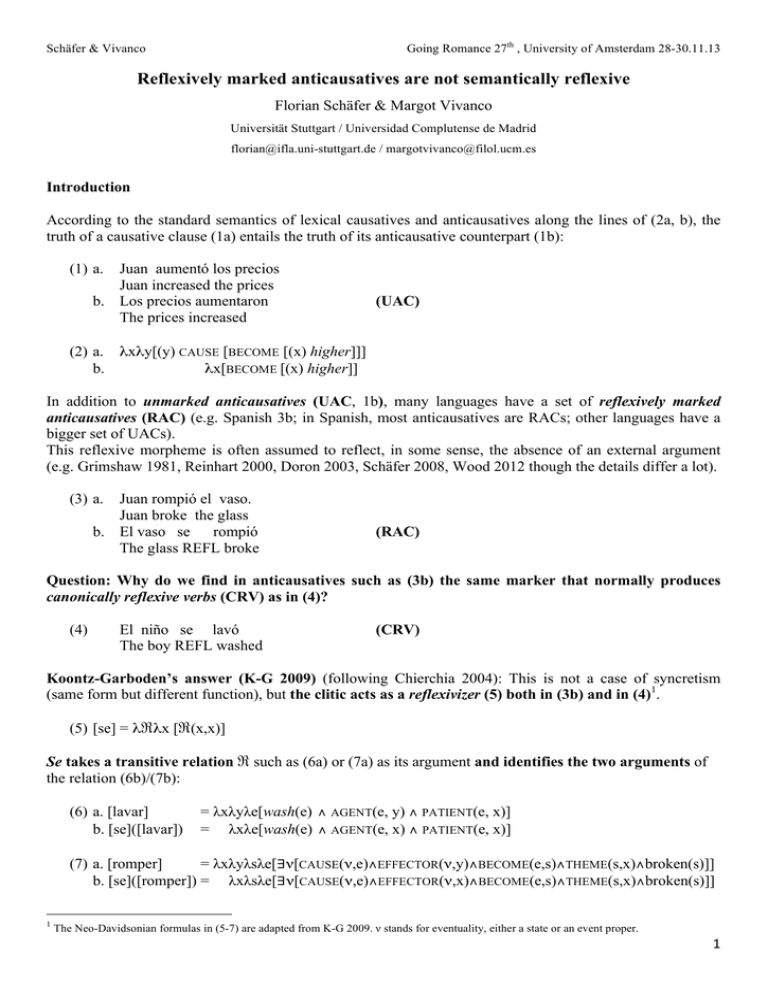

Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 Schäfer & Vivanco Reflexively marked anticausatives are not semantically reflexive Florian Schäfer & Margot Vivanco Universität Stuttgart / Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] / [email protected] Introduction According to the standard semantics of lexical causatives and anticausatives along the lines of (2a, b), the truth of a causative clause (1a) entails the truth of its anticausative counterpart (1b): (1) a. Juan aumentó los precios Juan increased the prices b. Los precios aumentaron The prices increased (UAC) (2) a. λxλy[(y) CAUSE [BECOME [(x) higher]]] b. λx[BECOME [(x) higher]] In addition to unmarked anticausatives (UAC, 1b), many languages have a set of reflexively marked anticausatives (RAC) (e.g. Spanish 3b; in Spanish, most anticausatives are RACs; other languages have a bigger set of UACs). This reflexive morpheme is often assumed to reflect, in some sense, the absence of an external argument (e.g. Grimshaw 1981, Reinhart 2000, Doron 2003, Schäfer 2008, Wood 2012 though the details differ a lot). (3) a. Juan rompió el vaso. Juan broke the glass b. El vaso se rompió The glass REFL broke (RAC) Question: Why do we find in anticausatives such as (3b) the same marker that normally produces canonically reflexive verbs (CRV) as in (4)? (4) El niño se lavó The boy REFL washed (CRV) Koontz-Garboden’s answer (K-G 2009) (following Chierchia 2004): This is not a case of syncretism (same form but different function), but the clitic acts as a reflexivizer (5) both in (3b) and in (4)1. (5) [se] = λℜλx [ℜ(x,x)] Se takes a transitive relation ℜ such as (6a) or (7a) as its argument and identifies the two arguments of the relation (6b)/(7b): (6) a. [lavar] = λxλyλe[wash(e) ∧ AGENT(e, y) ∧ PATIENT(e, x)] b. [se]([lavar]) = λxλe[wash(e) ∧ AGENT(e, x) ∧ PATIENT(e, x)] (7) a. [romper] = λxλyλsλe[∃ν[CAUSE(ν,e)∧EFFECTOR(ν,y)∧BECOME(e,s)∧THEME(s,x)∧broken(s)]] b. [se]([romper]) = λxλsλe[∃ν[CAUSE(ν,e)∧EFFECTOR(ν,x)∧BECOME(e,s)∧THEME(s,x)∧broken(s)]] 1 The Neo-Davidsonian formulas in (5-7) are adapted from K-G 2009. ν stands for eventuality, either a state or an event proper. 1 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 Some motivation for the reflexivization analysis of anticausatives (RAoAC): § There is only one 'se' with well-defined meaning. (Or: The meaning of 'se' remains constant). § The RAoACc does not violate Monotonicity: Monotonicity Hypothesis (Kiparsky 1982, K-G 2007, 2009): Word formation operations add, but do not remove, meaning. § The RAoAC derives the Underspecified External Argument Condition (UEAC): Underspecified External Argument Condition (e.g. Levin & Rappaport Hovav 1995, Reinhart 2002, AAS to appear): Only transitive verbs that do not restrict the θ-role of their external argument to agents enter the (anti)causative alternation: (8) a. El terrorista / *la enfermedad / *la bomba asesinó al presidente. The terrorist / the disease / the bomb murdered the president b. *El presidente se asesinó por sí solo The president REFL murdered by itself (non-anternating transitive) (9) a. (alternating transitive) Los vándalos / las piedras / la tormenta rompió la ventana. The vandals / the rocks / the storm broke the window. b. La ventana se rompió por sí sola The window REFL broke by itself Thus, the only difference between CRVs and RACs concerns the external argument θ-role: verbs like romper select an underspecified effector (cf. 7a) lacking any agent entailments, therefore the nonhuman theme 'the glass' in (3b/9b) can also be assigned this external effector role: Ø According to the RAoACs, (3b/7b/9b) mean that 'the glass caused its own breaking'. Ø According to the RAoAC, UACs as in (1b) are semantically not reflexive but inchoative, just like unquestionable inchoative structures, e.g. 'The water became cold'. (Caveat: For individual UACs, K-G (2009) and Beavers & K-G (2012) leave open the possibility, that they could involve a covert reflexivizer).2 Our claim: RACs do not have the causative-reflexive meaning in (7b) but the inchoative one in (2b). From this it follows that: § RACs form a semantically uniform class together with UACs and other clearly inchoative structures (‘pure’ unaccusative verbs, copula+adjective). § The reflexive morpheme does not always act as a reflexivizer/bound anaphor. § Nothing (except world knowledge) blocks reflexivization of (2a). Therefore, a surface string such as (3b) can, in principle, receive the reading in (7b), but only under very specific circumstances. The account in (7a, b), on the other hand, wrongly predicts meaning (2b) to be generally unavailable for RACs (section 2). Note: In this talk, we will deal just with Spanish data, but our evidence comes from German, too, where all results discussed below can be replicated. 2 This idea is not as innocent as suggested by these authors as English zero derived reflexive verbs denote 'naturally reflexive' events while languages with SE-anaphors lack zero-derived reflexive verbs of the English type (John washed) altogether (see Alexiadou et al., in prep). 2 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 Some first challenges for the RAoAC3 § Romance languages use the reflexive clitic for a wide range of constructions (cf. Spanish 10-13; see also Horvath & Siloni 2012). It is not clear how these could involve a reflexivization process / operator, so morphological identity does not necessarily reflect semantic identity: (10) Se venden pisos. REFL sell3rd.pl flats (reflexive passive) (‘Flats are sold’, i.e. ‘flats for sale’). (11) Estas patatas se cortan fácilmente. These potatoes REFL cut easily (generic middle) (‘These potatoes cut easily’) (12) Se vive bien en Madrid. REFL live.3rd.sg well in Madrid (reflexive impersonal) (‘One lives well in Madrid’). (13) Juan se comió la tarta. Juan REFL ate the cake. (so called “aspectual se”) (‘Juan ate the cake up’) § The RAoAC does not account for the syntactic differences between RACs and CRVs: Schäfer (2008) and Pitteroff & Schäfer (to appear) show for German that the nominative DP is merged as an internal object argument in RACs, while it is merged as an external subject argument in CRVs. 1. Probing the semantics of RACs via negation A consequence of the reflexive analysis of RACs: the truth of the causative clause does not entail the truth of its RAC counterpart (i.e. a vase can be caused to break without the vase causing its own breaking, just as a boy can be washed without him washing himself.) K-G sees this prediction confirmed in examples such as (14), where a RAC is negated while its transitive counterpart is asserted: (14) El vaso no se rompió, lo rompiste tú. The glass no REFL broke, it broke you (K-G 2009) (‘The vase didn’t break, you broke it.’ ) Question: But doesn’t (14) involve Metalinguistic Negation (MN)? Note that (2a,b) force the negation in (14) and (17) to be interpreted as metalinguistic, since logical negation would lead to a contradiction. (7a, b) predict that logical negation is possible with (14) and (17). • K-G’s answer: NO (from A + B + C). A. MN does not license NPIs (15) (Horn 1985). (15) a. John didn’t manage to solve SOME of the problems, he solved them all. b. *John didn’t manage to solve ANY of the problems, he solved them all. B. Spanish ningún is an NPI as it cannot appear in a context like (15), as shown in (16b), 3 AAS (to appear) discuss further problems for the RAoAC; these involve overgeneration concerning the availability of reflexive morphology (every UAC is predicted to have also a RAC version) and the lack of anticausatives of 'destroy'-verbs in many languages, the need of two explanations for the UEAC (one for marked and one, in addition, for unmarked anticausatives) and, as partly already discussed in Horvath & Siloni (2011, 2013), a number of wrong empirical predictions concerning the licensing of intensifiers, 'by itself', oblique causers and causer PPs. 3 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 (16) a. ¡No consiguió resolver ALGÚN problema, consiguió resolverlos todos! No managed to.solve some problem, managed to.solve.them all ‘(S)/he didn’t manage to solve some problem, (s)he managed to solve them all!’ b. *No consiguió resolver NINGÚN problema, consiguió resolverlos todos. No managed to.solve any problem, managed to.solve.them all C. but ningún CAN be licensed in a context like (14), as shown in (17). Ø Therefore, both (14) and (17) are instances of logical negation, which is only possible/noncontradictory if the causative construction does not entail the truth of its RAC counterpart. (17) No se rompió NINGÚN vaso, los rompiste todos tú. No REFL broke any glass, them broke all you. ‘There didn’t break any glass, you broke them all.’ • Our answer: YES, (14) and (17) do involve MN. We refute the argument from (16b) in two steps: A. Metalinguistic negation involves scalarity. MN negates the assertability of an utterance by means of removing the upper bounding conversational implicature associated with scalar predications. Such implicatures are driven by Grice’s maxim of Quantity (be as informative as required). (18) a. Luisa no odia a los niños, los aborrece. Luisa no hates toACC the children, them loathe ‘Luisa doesn’t hate children, she loathes them.’ b. El agua no está templada, está caliente. The water no is warm, is hot 'The water isn’t warm, it is hot’. c. Algunos hombres no son chovinistas, todos los hombres son chovinistas. Some men no are chauvinists, all the men are chauvinists ‘Some men aren’t chauvinists, all men are chauvinists.’ d. Pepe no tiene tres hijos, tiene cuatro. Pepe no have three children, has four ‘Pepe doesn’t have three children, he has four.’ B. Ningún is not an NPI, but a negative quantifier which also triggers negative concord (e.g. Bosque 1980, de Swart 2010). The claim that ningún is an NPI (15-17) is problematic because it is licensed in clear cases of MN4: (19) Luisa no odia a ningún niño, los aborrece a todos. Luisa no hates toACC any child, them loathes toACC all ‘Luisa doesn’t hate any child, she loathes them all.’ The contrast between (16b) and (19) is expected because: 4 Odiar (‘hate’) and aborrecer (‘loathe’) are in a scalar relationship: odiar > aborrecer. (i) (ii) a. Víctor odia a Rocío, pero no la aborrece. (‘Víctor hates Rocío, but he doesn’t loathe her’) b. #Víctor aborrece a Rocío, pero no la odia. (Víctor loathes Rocío, but he doens’t hate her’) a. Víctor odia a Rocío, de hecho incluso la aborrece. (Víctor hates Rocío, in fact he even loathes her’) b. #Víctor aborrece a Rocío, de hecho incluso la odia. (‘Víctor loathes Rocío, in fact he even hates her’). 4 Schäfer & Vivanco § Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 A negative quantifier (cf. English no) differs from an existential one (cf. English some) in that it does not trigger, by itself, any implicature that could be metalinguistically negated in (16b). (20) a. For no problem, it is the case that John managed to solve it. #John actually managed to solve all of them. b. For some problems, it is the case that John managed to solve them. John actually managed to solve all of them. § In (19), however, the verb pair makes available such an upper bounding implicature (only hate vs. even loathe). (21) For no child, it is the case that John hates it. John actually loathes all of them. Ø Causative-anticausative pairs do exactly the same under the semantics in (2a, b). The RAC in (14) and (17) is semantically inchoative and triggers the implicature that the corresponding causative is too strong. MN negates this upper bound. In the following sections we provide further evidence to show: i) that (14) involves MN, ii) that RACs behave semantically like UACs, and unlike CVRs. 1.1. Solo (‘just’). (14) licences solo (the Spanish counterpart of English ‘just’) (see 22), which is typical for MN (Horn 1985) but odd with logical negation (23): (22) El vaso no solo se rompió, tú lo rompiste. The glass not just REFL break, you it broke ‘The glass didn’t just break, you broke it.’ (23) #El niño no solo se lavó, tú lo lavaste. The child not just REFL washed, you him washed ‘#The child didn’t just wash, you washed him.’ 1.2. Pero vs. sino (que) (concessive vs. corrective ‘but’) Conjunctions like English but diagnose MN (Horn 1985, Koenig & Benndorf 1998).5 But has a concessive (but1) and a corrective (but2) use and both are overtly distinguished in Spanish (pero vs. sino que) (as well as in German: aber vs. sondern). While 'logical' negation allows but1 and but2 (24), MN only licenses but2, (25). (24) Pepe no es rico, {pero / sino que} es inteligente. Pepe no is rich, but1 / but2 is intelligent. ‘Pepe is not rich but1/but2 he is intelligent’. (logical negation) 5 The test in this section can be applied to other languages, too, such as English, Norwegian or French. (Many thanks to Gillian Ramchand and Fabienne Martin for pointing this out to us.) For example, English 'but' only has a concessive use as in (i) and (ii), Since it lacks a corrective use, it is out in metalinguistic negations (iii). It shows then that English anticausatives are not semantically reflexive. (i) He is not rich, (but) he is intelligent. (ii) The child did not wash (herself) (but) the mother washed her. (iii) It is not warm in here (#but) it is actually hot. (iv) The vase did not break (#but) you broke it. 5 Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 Schäfer & Vivanco (25) a. El agua no está templada, {#pero / sino que} está caliente. (metalinguistic negation) The water no is warm but1 / but2 that is hot ‘The water is not warm, but2 it is hot’. b. Luisa no odia a ningún niño, {#pero / sino que} los aborrece a todos. Luisa no hates toACC no/any child, but1 / but2 that them loathes toACC all ‘It is not the case that Luisa hates no child, she loathes them all.’ Ø Note that in (25b) ningún is licensed while pero is not. If both elements were disallowed in the context of MN, this would be unexpected, but it follows from the fact that ningún is not an NPI but a negative quantifier and, therefore, available in MN. This test shows that RACs (26a) behave like other inchoative predicates -UACs (b), pure unaccusatives (c) and combinations of a copula with an adjective (d)6, involving MN and rejecting logical negation; they do not behave like CRVs (27): (26) a. El vaso no se rompió, {#pero / sino que} tú lo rompiste. The glass no REFL broke but1 / but2 that you it broke b. Los precios no aumentaron, {#pero / sino que} tú los aumentaste. The prices no increased but1 / but2 that you them increased c. El rosal no floreció, {#pero / sino que} el jardinero lo hizo florecer. The rosebush no blossomed but1 / but2 that the gardener it made blossom d. El niño no se puso enfermo, {#pero / sino que} tú lo infectaste. The kid no REFL get sick but1 / but2 that you him infected (27) El niño no se lavó, The kid no REFL washed {pero / sino que} lo lavó la niñera. but1 / but2 him washed the nanny 1.3. Real NPIs: siquiera (‘not even’) Examples such as (14) and (17) are instances of MN, they allow ningún because it is a negative quantifier, but they disallow real NPIs, as expected if they involve metalinguistic negation. This test gives exactly the same results as the previous one in (26-27). A basic example of a MN rejecting this NPI (28): (28) #Luisa no odia siquiera a los niños, los aborrece. Luisa no hates not.even toACC the children them loathes ‘Luisa doesn’t (even) hate children (at all), she loathes them’. The RAC in (29a) cannot combine with the NPI siquiera (‘not even’)7, thereby behaving like other inchoative predicates such as UACs (b) as well as pure unaccusatives (c) and combinations of an eventive copula with an adjective (d). CRVs (30), on the other hand, are compatible with the NPI, as predicted by (6a, b) (and wrongly by (7a, b) for RACs), since the negation must be interpreted as logical. 6 The Spanish counterparts of English ‘become’ take se (ponerse, volverse), which makes them tricky for our purposes here. German examples such as (i) proof our point in a clearer way. (i) DasKind ist nicht krank geworden, {#aber / sondern} du hast es angesteckt. The child is not sick become, {#but1 / but2} you have it infected it 'The child did not get sick, you infected it'. 7 Horvath & Siloni (2011) argue that the Spanish NPI en absoluto (‘at all’) cannot appear in examples like (14). However, Beavers & K-G (2013) report judgments that suggest that en absoluto can escape standard conditions on NPI licensing (cf. Giannakidou 2006, 2011). Siquiera does not face such problems. 6 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 (29) a. #El vaso no se rompió siquiera, tú lo rompiste The glass no REFL broke not.even you it broke ‘The glass didn’t (even) break (at all), you broke it.’ b. #Los precios no aumentaron siquiera, tú los aumentaste. The prices no increased not.even, you them increased ‘The prices didn’t (even) increased (at all), you increased them.’ c. #El rosal no floreció siquiera, el jardinero lo hizo florecer. The rosebush no blossomed not.even, the gardener it made blossom ‘The rosebush didn’t (even) blossom (at all), the gardener made it blossom.’ d. #El niño no se puso enfermo siquiera, tú lo infectaste. The child no REFL get sick not.even, you him infected ‘The child didn’t (even) get sick (at all), you infected him.’ (30) El niño no se lavó siquiera, lo lavó la niñera. The kid no REFL washed not.even him washed the nanny ‘The kid didn’t (even) wash (at all), the nanny washed him.’ 1.4. Ningún and UACs: a potential counter-argument Another consequence of K-G’s analysis: UACs and RACs should differ semantically (2b vs. 7b). K-G sees this claim confirmed in the following contrast: ningún is allowed with RACs (17), repeated below, while it is not with UACs (31). He argues that since UACs are entailed by their causative counterpart, (31) involves MN (not logical negation). (31) rejects ningún because, as an NPI, it is not compatible with MN. (17) No se rompió NINGÚN vaso, los rompiste todos tú. No REFL broke any/no glass, them broke all you ‘There didn’t break any/no glass, you broke them all.’ (31) #No empeoró ningún paciente, los empeoró a todos el tratamiento. No worsened any/no patient, them worsened to all the treatment ‘No patient worsened, the treatment worsened them all.’ If this is indeed correct, there would be two consequences for us: § If UACs as in (31) license MN but do not license ningún, our claim that ningún is not a NPI is problematic. § If there are indeed semantic differences between RACs and UACs, the semantic formula in (2b) could not be the correct description for both of them. However, we find the judgment in (31) wrong. Ø In our opinion, both RACs and UACs can license ningún without any problems. The following examples have been tested with 21 native Spanish speakers: (32) [In a trial on medical negligence] Judge: El doctor García ha afirmado que los pacientes en cuarentena empeoraron repentinamente por sí solos, ¿está usted de acuerdo con esta afirmación? (‘Dr. García has said that the patients in quarantine worsened suddenly by themselves, do you agree with this claim?’) 7 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 Witness: No empeoró ningún paciente (por sí solo), (sino que) los empeoró a todos el tratamiento No worsened no patient (by himself), (but2 that) them worsened to all the treatment experimental proporcionado por el doctor García. experiemental provided by the doctor García. (‘There didn’t worsen any patient (by himself, (but2) Dr. García’s experimental treatment worsened them all’). (33) [In the butcher’s shop] Lady: ¡Uy! ¡Qué cara está la carne! (‘Oh! How expensive is the meat!’) Butcher: La semana pasada aumentaron algunos precios. The last week increased some prices Lady: ¡No aumentó ningún precio, (sino que) los aumentó todos usted, so ladrón! No increased no price (but2) them increased all you, such thief. (‘There didn’t increased any price, (but2) you increased them all, you thief!’) This shows again that RACs and UACs do not differ semantically: they both have the semantics in (2b).8 2. Is the reflexive reading totally impossible for RACs? We have argued against the reflexivization analysis of RACs, proposing that they have the inchoative semantics in (2b). But, can't strings as (3b), at least optionally, have a reflexive construal derived from (2a) via reflexivization/a semantically bound anaphor? § This option cannot be blocked by formal grammar because reflexivization is a productive process available, formally, for all transitive verbs. § Instead, we think that it is blocked by conceptual considerations: such a construal is as nonsensical as the English 'The glass broke itself' (see e.g. Stephens (2006) for a construction which shows that the English SELF-reflexive has no human restriction). § But in specific contexts, if the nonsensical construal is negated and/or enforced by an intensifier (Spanish sí mismo ‘itself’), it becomes available as the licensing of but1 and but2 in (34) shows. Ø Crucially, note that (34a) has nothing to do with anticausativization, since UACs as in (1b) enter the reflexive construal under such conditions, too (34b). (34) a. El vaso no se rompió a sí mismo, lógicamente, {pero / sino que} tú lo rompiste. The glass no REFL broke to himself logically but1 / but2 that you it broke ‘The glass didn’t break itself, logically, but1/but2 you broke it.’ b. Los precios no se aumentaron a sí mismos, lógicamente, {pero/sino que} Ana los aumentó. The prices no REFL increased to themselves logically but1/but2 that Ana them increased ‘The prices didn’t increase themselves, logically, but1/but2 Ana increased them.’ 8 The class of UACs is extremely small in Spanish and most unmarked unaccusative verbs lack a causative variant. We note that 20 out of 21 consultants agreed with the judgment in (32) while only 13 of them agreed with (33). Of course, we expect that speakers that lack a transitive, causative version of the verbs under consideration reject examples such as (31)-(33). We suspect that this is the problem with speakers who do not accept examples such as (31-33). 8 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 3. Outlook: Probing other reflexively marked structures for their semantics: psych verbs We think that the tests we developed above (building on K-G 2009) can be helpful to identify the semantics of other verb classes involving reflexive morphology. Spanish psych verbs can enter both a transitive (causative) construction (35a) and an intransitive construction marked with the reflexive clitic se (35b)9: (35) a. {El profesor / la película} aburrió a Luisa. The teacher / the film bored to.acc Luisa ‘The teacher / the film bored Luisa.’ b. Luisa se aburrió (con la película). Luisa REFL bored with the movie ‘Luisa got bored (about the movie).’ Question: What role is the clitic se playing in (35b)? Is it an anticausative se, a truly reflexive se or something else? Our tests suggest that the (35b) has inchoative semantics along the lines of (2b), and not reflexive semantics along the lines of (7b): Solo: (36) Luisa no solo se aburrió, la aburrió {el profesor / la película}. Luisa not just REFL bored her bored the teacher the film ‘Luisa didn’t just get bored, the teacher / the film bored her.’ Pero / sino que: (37) Luisa no se aburrió, {#pero / sino que} la aburrió {el profesor / la película}. Luisa not REFL bored but1 but2 that her bored the teacher the film ‘Luisa didn’t get bored, but2 the teacher / the film bored her.’ Siquiera: (38) #Luisa no se aburrió siquiera, la aburrió {el profesor / la película}. Luisa not REFL bored not.even her bored the teacher the film ‘Luisa didn’t (even) get bored (at all), the teacher / the film bored her’. Our tests show that the pair in (35) allows only MN, thus behaving like causative / inchoative pairs, and not like CRVs. Note: (i) reflexively marked psych verbs do not necessarily all have the same semantics so that it should not be surprising if some turn out to be semantically reflexive (e.g. s'encourager in French or German). (ii) there are also differences between inchoative psych verbs and anticausatives. In particular, once we add the so-called 'subject matter' PP (see the PP in (35b); cf. Pesetsky 1995) to the reflexive structures, our tests collapse. 9 Typically, Spanish psych verbs can enter a third construction in which the experiencer is spelled out as a dative in initial position, and the source of the psychological emotion is spelled out as a postverbal nominative subject. This construction is mainly used with a stative meaning: (i) A Luisa le aburren las películas. To.Luisa.DAT cliticDAT bores.3rd pl. the moviesNOM (i.e. ‘Luisa dislikes movies, as they bore her’). 9 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 4. Conclusions We have argued that RACs have the inchoative meaning in (2b), and not the reflexive one in (7b). From this we derive three conclusions: 1) The truth of the causative entails the truth of its anticausative counterpart. - Thus, the latter can be negated while the former is asserted iff the negation is metalinguistic, not logical. - This claim is supported by the distribution of pero (concessive ‘but’) and true NPIs such as siquiera, both disallowed in MN contexts. - Negative concord elements such as ningún are not NPIs as they are allowed in canonical MN contexts such as (19). 2) RACs form a semantically uniform class together with UACs and other inchoative constructions. RACs pattern together with inchoative structures with regard to all the tests presented above, they do not pattern together with CRVs as expected if (7a,b) was correct. 3) The morphological identity between marked anticausatives and canonical reflexive verbs does not reflect semantic identity between the two constructions. Therefore, the clitic se does not always act as a reflexivizer/bound anaphor. We face a real syncretism. For reasons of time we can not even address any of the many remaining questions concerning the role of se in anticausatives, the reasons that might underlie this syncretism, or the reasons driving the split between marked and unmarked anticausatives. For different proposals and further references, see e.g. Grimshaw (1981), Reinhart (2002), Doron (2003), Reinhart & Siloni (2005), Schäfer (2008), Wood (2012) or AAS (to appear), among many others. References Alexiadou, A., E. Anagnostopoulou & F. Schäfer (to appear). External arguments in transitivity alternations: a layering approach. Oxford University Press. Alexiadou, A., F. Schäfer & G. Spathas (in prep.). Delimiting Voice in Germanic: on object drop and naturally reflexive verbs. Proceedings of NELS 44. Beavers, J. & A., Koontz-Garboden 2013. In defense of the reflexivization analysis of anticausativization. Lingua 131:199-216. Bosque, I. 1980. Sobre la negación, Madrid, Cátedra. Chierchia, G. 2004. A semantics for unaccusatives and its syntactic consequences. In A. Alexiadou, et al. (eds.), The unaccusativity puzzle: explorations of the syntax-lexicon interface, 22-59. Oxford: OUP. Doron, E. 2003. Agency and Voice: the semantics of the Semitic templates. Natural Language Semantics, 11(1), 1-67. Giannakidou, A. 2006. Only, emotive factives, and the dual nature of polarity dependency. Language, 82: 575-603. Giannakidou, A. 2011. Positive polarity items and negative polarity items: variation, licensing, and compositionality. In Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning (Second edition); ed. by C. Maienborn, K. von Heusinger, and P. Portner). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Grimshaw, Jane. 1981. On the lexical representation of Romance reflexivie clitics. In The Mental Representation of Grammatical Relations, ed. Joan Bresnan, 87–148. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Horn, L. R. 1985. Metalinguistic negation and pragmatic ambiguity. Language 61:121-174. Horvath , J & T. Siloni 2011. Anticausatives: Against Reflexivization. 2011. Lingua 121, 2176-2186. Horvath, J. & T. Siloni2013. Anticausatives have no Cause(r): A Rejoinder to Beavers and KoontzGarboden. To appear. Lingua. 131, 217-230 Kiparsky, P. 1982. Word-formation and the lexicon. In Proceedings of the 1982 Mid-America Linguistic Conference, ed. by F. Ingeman, 3–29. 10 Schäfer & Vivanco Going Romance 27th , University of Amsterdam 28-30.11.13 Koenig, J.-P. & B. Benndorf. 1998. Meaning and context: German aber and sondern in Discourse and Cognition: Bridging the gap, CSLI publications: Stanford, pp.365-386. Koontz-Garboden, A. 2007. States, changes of state, and the Monotonicity Hypothesis Ph.D. Dissertation, Stanford University. Koontz-Garboden, A. 2009. Anticausativization. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 27:77-138. Levin, B., & M. Rappaport Hovav 1995. Unaccusativity. At the Syntax-Lexical Semantics Interface. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Pesetsky, D. 1995. Zero syntax: Experiencer and cascades. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Pitteroff, M. & F. Schäfer. to appear. The argument structure of reflexively marked anticausatives and middles: Evidence from datives. In Proceedings of NELS 43. Reinhart, Tanya. 2000. The Theta System: syntactic realization of Verbal concepts. OTS working papers TL-00.002, Utrecht University. Reinhart, T. 2002. The Theta System – An Overview. Theoretical Linguistics 28: 229-290. Reinhart, T., & T. Siloni. 2005. The Lexicon-Syntax Parameter: Reflexivization and Other Arity Operations. Linguistic Inquiry 36:389–436. Schäfer, F. 2008. The Syntax of (Anti-)Causatives. External arguments in change-ofstate contexts. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Swart, H.E. de. 2010. Expression and interpretation of negation: an OT typology. Dordrecht: Springer. Stephens, N. 2006. Agentivity and the virtual reflexive construction. In B. Lyngfelt & T.Solstad (eds.), Demoting the agent: Passive, middle and other voice phenomena. Amsterdam, 275- 300. John Benjamins. Wood, J. 2012. Icelandic Morphosyntax and Argument Structure. Dissertation, NYU. 11