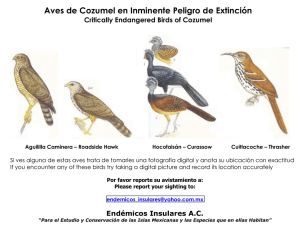

the journal of caribbean ornithology

Anuncio