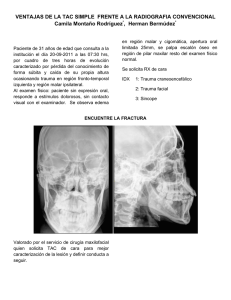

Physiopathology and treatment of critical bleeding

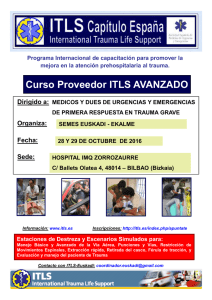

Anuncio