Investigación institucional de la opinión pública y dispositivos

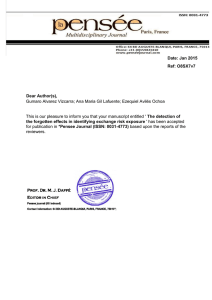

Anuncio