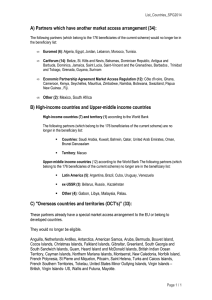

EUROPE`S OUTERMOST REGIONS AND THE SINGLE

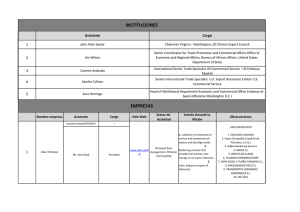

Anuncio