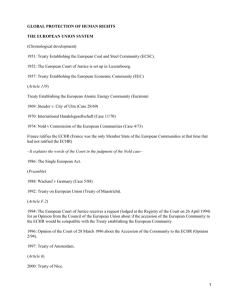

The interpretation of Article 51 of the EU Charter of Fundamental

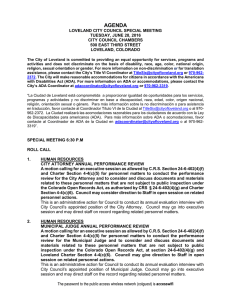

Anuncio