Avaluació d`intervencions terapèutiques no farmacològiques

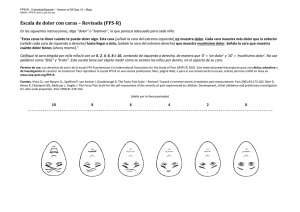

Anuncio