Multiple selection lists: “Check-all that apply” versus

Anuncio

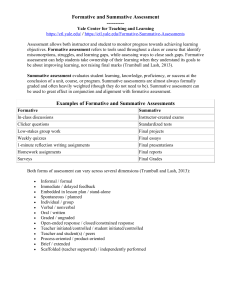

6th (In)formative Capsule Multiple selection lists: “Check-all that apply” versus “forced-choice” In any type of questionnaire it is usually necessary to ask the respondent to choose several options in a set of available alternatives. A typical format for this kind of questions is the “check-all-that-apply”; it is used when we have a list – generally a long one – of items in which we might want to know all the answers that apply for each respondent. For example, from a list of n brands we would like to know which ones the respondent knows and which ones have been bought during the last 12 months, or which alternatives the respondent would recommend. In a similar way, from a list of n activities, we could ask which options the respondent practise at least once a week, or the activities he/she has done at least once in his/her life, etc. The “check-all-that-apply” questions are usually presented like this: Q1- Please, tick all the brands you have bought during the last 12 months: Brand 1 Brand 2 … Brand n In online questionnaires, the element that allows respondents to tick each item (named as “input type”) is normally a “checkbox”, which is a squared box that can be selected and unselected easily by clicking on it. Using this element to choose more than one option from a list is a standard of web communication. An alternative way to ask the same question is to list each item and request the respondent to answer “yes” or “no” for each of them. This kind of question is known as “forced-choice format” because the respondent must indicate whether this applies or not. It is usually presented as following: Q1alternative- Please, for each of the following brands indicate whether you have bought or not these brand products in the last 12 months: Brand 1 Brand 2 … Brand n Yes ○ ○ ○ ○ No ○ ○ ○ ○ In order to have an enquiry with this format in an online questionnaire it is normally used pairs of “radio-buttons”; one for the option “yes” and the other for the option “no”. The “radio1/4 6th (In)formative Capsule buttons” have a circular shape and only allow selecting one element of the group. So, when one “radio-button” is picked, the rest become automatically unavailable (in this case, if we pick “yes” we won’t be able to pick “no” as it will be blocked and vice versa). This does not mean that the respondent will not be able to change the chosen answer. In face-to-face surveys (CAPI) or phone surveys (CATI), the second alternative “forced-choice” is more used as it would be very difficult for the responder to hear a long list of items and remember all the options that apply in order to number them at the end. It is much easier to answer “yes” or “no” as the respondent listen to each item, before moving on to assess the next one. However, on paper or online surveys where the respondent can see all the items written on the paper or on the screen this memory problem does not exist. That is why a lot of surveys use the format “check-all-that-apply”. Often, both formats are used as if they were equivalent or interchangeable. Many researchers when they migrate surveys from paper to CAPI/CATI or from CAPI/CATI to online, they only transform questions from one format to the other, without worrying about the consequences that this change can have in the results. Otherwise, the differences that exist between the data produced by both formats using the alternative “check-all-that-apply”, is that if the respondents do not make enough effort to answer properly the question (reading and evaluating conveniently each of the given options), we could encourage them to choose less items than the ones that really apply (known by “weak satisficing”). In this way, a respondent that selects 3 options from a list of 10, may think that he/she has done his/her duty and that it is not necessary to keep making efforts in reading and evaluating all of the other options. On the other hand, it has been proven that people has tendency to answer yes1 (“acquiescence” or “yes-saying”) more often, so when we ask a respondent to indicate “yes” or “no” in a “forced-choice” format, we can cause respondents to choose more times “yes” than what in fact corresponds to reality. To make sure whether those phenomena occur in practice, Smyth et al (2006) compared 16 experiments in 2 online surveys and 1 on paper (2002-2003) in the United States of America. After analyzing the results, they found that the 2 formats do not act in an equivalent way: the respondents choose more items whit the “yes/no” format, rather than when using a “checkall-that-apply” format. The Smyth et al (2006) shows that the problem comes from the “satisficing” experimented in the “check-all-that-apply”, and not from the tendency of answer “yes” in the format “yes/no”. Therefore, they conclude that the format “forced-choice” is preferable, or in other words, it gets results that are closer to reality. Since both, the tendency of saying “yes” and the “weak satisficing”, can vary between countries, in Netquest – within the scope of the research project of R2online.org – we have carried out experiments in different countries of the Ibero-America region: Spain, Mexico and 1 As seen in the 5th (In)formative Capsule: The use of balanced questions reduces the impact of the tendency of respondents to answer "yes" 2/4 6th (In)formative Capsule Colombia. In table 1, we can observe a list of 7 items asking about political activities (e.g.: whether the respondent has ever signed a petition to a government, whether the respondent has ever contact a politician…). Here we can see an average of how many times the respondents said yes with the format “yes/no” and with the format “check-all-that-apply”, in each of the 3 countries. Table 1: Average of items selected out of the 7 items of the matrix Mexico Yes/N CATA o Average number of items to those who said “yes” 1.88 1.53 Colombia Spain Yes/No CATA Yes/No CATA 2.06 1.70 2.10 1.60 Note: CATA = check-all-that-apply The results are similar to those obtained by Smyth et al (2006): there are more political actions reported when using format “yes/no” than when using the “check-all-that-apply” format. It is clear that the format “check-all-that-apply” collects more mentions, but ¿which information is more real? To know which of these 2 formats is preferable, we have performed a test of external validity, considering the correlations between the total number of items that a respondent affirms to have done and a variable with which theoretically should find a high correlation; in this case, we use a question about the interest that the respondent has towards politics (B1- To what extend would you say you are interested in politics? A lot, quite a lot, not much, not at all). Supposedly, the greater interest in politics the higher number of activities related to politics should be observed. Thus, the format that gets this correlation higher is the one we should consider as preferable. Table 2: Correlation between total number of selected items and the politics’ interest Mexico Colombia Spain Yes/N CATA Yes/No CATA Yes/No CATA o Correlation -.4175 -.3456 -.3739 -.3727 -.3663 -.3067 The correlations are similar in Colombia, but in Mexico and Spain are higher in the “yes/no” format”, which means that this format is more preferable than the “check-all-that-apply” one. Therefore, the experiments carried out in the Ibero-America region agree with the ones found by Smyth et al (2006) in USA. In conclusion, in different countries seem that respondents do not make the maximum effort to answer properly when the “check-all-that-apply” format is used, as they choose less items than the ones that really apply. Clearly, both formats are not equivalent and so they are not interchangeable. 3/4 6th (In)formative Capsule Bibliographic references: Jolene D. Smyth, Don A. Dillman, Leah Melani Christian, and Michael J. Stern (2006). Comparing Check-All and Forced-Choice Question Formats in Web Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly (Spring 2006) 70(1): 66-77 doi:10.1093/poq/nfj007 4/4